Sam Brusco, Associate Editor05.30.19

The skilled labor shortage, which according to a Deloitte and Manufacturing Institute study threatens to render two million American manufacturing jobs vacant by 2025, has begun to affect the medical device industry.

Despite medtech’s potential for a rewarding career in an industry whose purpose is to save lives, there is still a stereotype associated with employment in the skilled trades. The perception that a factory job requires little skill or thinking and offers no advancement opportunities unfortunately still prevails, and popular culture doesn’t help—trade workers are still depicted as bumbling, poor, uneducated, lazy, and rude.

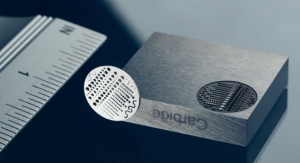

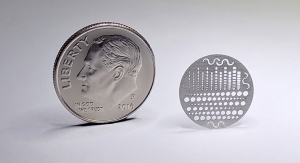

This is simply not true, especially in medical device manufacturing. Today, skilled tradespeople working to build medical devices and components need strong technical know-how and experience to operate complex part fabrication machinery. To work in medical manufacturing, prospective employees must often complete work-based learning programs, undergo an apprenticeship program, or obtain an associate’s degree.

But changing the attitude toward the skilled trades is only the first step to build a competent and, more importantly, passionate medical manufacturing workforce. Medical manufacturing companies must also do their part to recruit and retain employees. It can cost significant time and effort to implement workforce development programs, but without them the skilled labor shortage will continue to decline.

To gain more insight into how medtech manufacturers are attracting and developing a passionate workforce, I spoke with John MacDonald, president of AIP Precision Machining, a Daytona Beach, Fla.-based provider of precision machining services for the medical device industry. The breadth of his input was not included in the recent feature article entitled “The Human Factor: How Medtech Firms Are Battling the Labor Shortage” (which can be read here), so the entirety of our discussion is included in the Q&A below.

Skilled tradespeople working to build medical devices and components need strong technical know-how and experience to operate complex machinery.

Sam Brusco: What efforts, if any, does your company make to reach out to schools to generate interest in the industry? (Colleges, trade schools, high schools, even middle or grade schools?)

John MacDonald: We have had a mixed-bag response from such efforts. We are partnered with a local advanced training center who included machining as one of their courses of study. To date, we have hired two machinists from the program with fair results. In the past, we have hired engineering students from local colleges, some of which came to us with excellent work ethic and a desire to learn the trade. However, these employees were later hired off at other companies which offered more formalized engineering programs. At the end of the day, machining is a “blue collar” trade. Unfortunately, as a society we have mentally downgraded the image of blue collar workers. Inevitably this resulted in many of our children looking toward desk jobs rather than trade jobs to alleviate the misaligned stigma that a career in the trades is substandard.

Brusco: Is there a way industry can get involved in the classrooms for a STEM program?

MacDonald: Perhaps mentoring programs or tradespeople visiting the classes. However, I have found the majority of machinists to be more introverted and therefore less interested in taking on classroom type mentoring. Of course, this is my opinion and doesn’t reflect the total machinist population…so apologies to you extroverted machinists out there, we just don’t have many of them here. Some sort of visiting program could perhaps entice more candidates to the field, however any shop I have been through seems to always be too busy (in reality) to participate in such events. It is not right, as we will never help increase the ranks without this type of promotion.

Brusco: What education and training do you offer to enhance the expertise of your workforce? Is there a minimum “term of service” with your company once a training/educational program has been completed?

MacDonald: All of our training is on the job. We link new candidates with shop leads or mentors. At the end of the day, it is up to the new employee to show their desire and ability to learn—when a senior machinist senses the desire and ability, they typically go out of their way to help transfer as many skills as possible to the lower level employee.

Brusco: What strategies do you employ regarding employee compensation and recognition to help retain your workforce?

MacDonald: We have next to zero employee turnover. I sometimes sarcastically say that although we are not located in a high compensation city, we pay better than if our shop was in Massachusetts, New York, or California. When we find good employees who exhibit loyalty, work ethic, attention to detail, capability, and ability to work well with others, we do all we can to keep those employees. My hope is that someday these highly gifted craftsmen (or artists) are compensated better than or equal to doctors, attorneys, and folks on Wall Street. Nothing against those professions, but when you make something custom, a one-of-a-kind work of art that provides part of the magic behind what makes the aircraft engine reliable, the medical procedure successful, extends a human life, or just in some way makes something in our world function better, why not compensate those talented individuals beyond the rates society perceives such work to be valued? Machinists make the world go round and have touched just about every product or modern marvel we know.

The value in making something, a part that you created and decided how to create, is not something found in all professions.

Brusco: How do you instill a sense of purpose (which is VERY important to the millennial workforce) in your employees to help ensure pride in their work and their retention?

MacDonald: Thank goodness our customers help do that every day via compliments on our work. I work very hard to keep the communication from the customer as direct to the floor as possible. This includes application details and many discussions regarding where the parts go, what it means for the end product or customer as well as feedback from the customer after receipt of our services. This is the key to the satisfied craftsman; there is the of course the base desire to manufacture a part to specification and efficiently as possible. Then there is the bigger picture of where the part goes and what value that craftsman’s work provided to propel the larger assembly to its proper function. When we sit back and think of where some of our parts are going or have been—in human bodies, in space, flying around the world every day, and keeping our military safer and more capable than ever before—that is when you realize the bigger picture than “just another part.”

Brusco: What future new efforts, if any, will you make to attract, educate/train, and/or retain your workforce?

MacDonald: I will continue my personal promotion of the financial and satisfying traits of being a top machinist/craftsman. This is all coming from someone who is not himself a machinist. Everyday our people go home knowing they made something. The value in making something, a part that you created and decided how to create, is not something found in all professions. Not to mention a custom manufacturing environment such as ours, where you are faced with new manufacturing challenges each and every day.

For more information on how the medical machining industry is attracting talent, John MacDonald is also quoted in my article "Smooth Operator: Addressing Machining's Talent Gap", which was featured in the January/February 2019 edition of MPO. Read it here!

Despite medtech’s potential for a rewarding career in an industry whose purpose is to save lives, there is still a stereotype associated with employment in the skilled trades. The perception that a factory job requires little skill or thinking and offers no advancement opportunities unfortunately still prevails, and popular culture doesn’t help—trade workers are still depicted as bumbling, poor, uneducated, lazy, and rude.

This is simply not true, especially in medical device manufacturing. Today, skilled tradespeople working to build medical devices and components need strong technical know-how and experience to operate complex part fabrication machinery. To work in medical manufacturing, prospective employees must often complete work-based learning programs, undergo an apprenticeship program, or obtain an associate’s degree.

But changing the attitude toward the skilled trades is only the first step to build a competent and, more importantly, passionate medical manufacturing workforce. Medical manufacturing companies must also do their part to recruit and retain employees. It can cost significant time and effort to implement workforce development programs, but without them the skilled labor shortage will continue to decline.

To gain more insight into how medtech manufacturers are attracting and developing a passionate workforce, I spoke with John MacDonald, president of AIP Precision Machining, a Daytona Beach, Fla.-based provider of precision machining services for the medical device industry. The breadth of his input was not included in the recent feature article entitled “The Human Factor: How Medtech Firms Are Battling the Labor Shortage” (which can be read here), so the entirety of our discussion is included in the Q&A below.

Skilled tradespeople working to build medical devices and components need strong technical know-how and experience to operate complex machinery.

John MacDonald: We have had a mixed-bag response from such efforts. We are partnered with a local advanced training center who included machining as one of their courses of study. To date, we have hired two machinists from the program with fair results. In the past, we have hired engineering students from local colleges, some of which came to us with excellent work ethic and a desire to learn the trade. However, these employees were later hired off at other companies which offered more formalized engineering programs. At the end of the day, machining is a “blue collar” trade. Unfortunately, as a society we have mentally downgraded the image of blue collar workers. Inevitably this resulted in many of our children looking toward desk jobs rather than trade jobs to alleviate the misaligned stigma that a career in the trades is substandard.

Brusco: Is there a way industry can get involved in the classrooms for a STEM program?

MacDonald: Perhaps mentoring programs or tradespeople visiting the classes. However, I have found the majority of machinists to be more introverted and therefore less interested in taking on classroom type mentoring. Of course, this is my opinion and doesn’t reflect the total machinist population…so apologies to you extroverted machinists out there, we just don’t have many of them here. Some sort of visiting program could perhaps entice more candidates to the field, however any shop I have been through seems to always be too busy (in reality) to participate in such events. It is not right, as we will never help increase the ranks without this type of promotion.

Brusco: What education and training do you offer to enhance the expertise of your workforce? Is there a minimum “term of service” with your company once a training/educational program has been completed?

MacDonald: All of our training is on the job. We link new candidates with shop leads or mentors. At the end of the day, it is up to the new employee to show their desire and ability to learn—when a senior machinist senses the desire and ability, they typically go out of their way to help transfer as many skills as possible to the lower level employee.

Brusco: What strategies do you employ regarding employee compensation and recognition to help retain your workforce?

MacDonald: We have next to zero employee turnover. I sometimes sarcastically say that although we are not located in a high compensation city, we pay better than if our shop was in Massachusetts, New York, or California. When we find good employees who exhibit loyalty, work ethic, attention to detail, capability, and ability to work well with others, we do all we can to keep those employees. My hope is that someday these highly gifted craftsmen (or artists) are compensated better than or equal to doctors, attorneys, and folks on Wall Street. Nothing against those professions, but when you make something custom, a one-of-a-kind work of art that provides part of the magic behind what makes the aircraft engine reliable, the medical procedure successful, extends a human life, or just in some way makes something in our world function better, why not compensate those talented individuals beyond the rates society perceives such work to be valued? Machinists make the world go round and have touched just about every product or modern marvel we know.

The value in making something, a part that you created and decided how to create, is not something found in all professions.

Brusco: How do you instill a sense of purpose (which is VERY important to the millennial workforce) in your employees to help ensure pride in their work and their retention?

MacDonald: Thank goodness our customers help do that every day via compliments on our work. I work very hard to keep the communication from the customer as direct to the floor as possible. This includes application details and many discussions regarding where the parts go, what it means for the end product or customer as well as feedback from the customer after receipt of our services. This is the key to the satisfied craftsman; there is the of course the base desire to manufacture a part to specification and efficiently as possible. Then there is the bigger picture of where the part goes and what value that craftsman’s work provided to propel the larger assembly to its proper function. When we sit back and think of where some of our parts are going or have been—in human bodies, in space, flying around the world every day, and keeping our military safer and more capable than ever before—that is when you realize the bigger picture than “just another part.”

Brusco: What future new efforts, if any, will you make to attract, educate/train, and/or retain your workforce?

MacDonald: I will continue my personal promotion of the financial and satisfying traits of being a top machinist/craftsman. This is all coming from someone who is not himself a machinist. Everyday our people go home knowing they made something. The value in making something, a part that you created and decided how to create, is not something found in all professions. Not to mention a custom manufacturing environment such as ours, where you are faced with new manufacturing challenges each and every day.

For more information on how the medical machining industry is attracting talent, John MacDonald is also quoted in my article "Smooth Operator: Addressing Machining's Talent Gap", which was featured in the January/February 2019 edition of MPO. Read it here!