Steve Maylish and Dave Mock, Fusion Biotec04.03.17

Outsourcing a complex medical design is a complicated process. Once a service provider is chosen, it’s not enough to pass the ball to the development team and follow the usual script of managing deadlines and checking progress. Anyone who’s managed a complex design project knows it’s difficult enough to assemble a qualified team and keep everyone engaged—the management metaphor often used is “it’s like herding cats.” For this reason, many firms rightly emphasize the need for system-focused project managers to drive a project to a successful conclusion.

In recent years, however, companies are realizing successful projects have more to do with the leadership skills—rather than the management skills—of the project manager. Much has been written about how to become a great leader and whether it comes naturally or can be learned through practice. It’s worth discussing the important qualities of a great project leader, but it can be even more valuable to highlight tools and methods that actually help develop and guide a team toward a leadership structure, rather than management.

Jeff Blanton writes in his book “Doing the Difficult—Boldly Leading Significant Change” that there are three C’s to project success: courage to inspire the team, capability to lead the team, and conviction to be successful.

In the book titled “Helping People Win at Work” by Ken Blanchard and Garry Ridge, the latter writes: “My leadership point of view is driven by my determination to make a difference, do worthwhile work, get good results, and, at the same time, have fun.”

If the team already trusts and respects the project manager, providing project leadership is not a large leap. Project leadership is a more nuanced process, but not necessarily more work.

Project leaders need soft skills in addition to leadership qualities. Most important is emotional intelligence, which encompasses self-awareness, self-regulation, social skills, empathy, and motivation. These traits enable a project leader to navigate team and stakeholder dynamics. Knowing one’s emotions, strengths, weaknesses, values, and goals and their impact on others, as well as controlling or redirecting disruptive emotions, moving team members toward a shared goal, considering other’s feelings, and being driven to reach goals for the sake of achievement—these encapsulate emotional intelligence.

Project leaders also need the ability to see the big picture, put the various stakeholders’ needs in context, negotiate and compromise, and collaborate with the team. The project leader must build trust and instill confidence in themselves and the team’s abilities. An early win on a project starts it off on a positive note and goes a long way to build confidence.

On the process side, technical project management is needed on both sides of the equation. But be careful, over-management can demoralize a team, while under-management can create a state of confusion. If the process of assembling a team or outsourcing is beginning, read my article titled “Specialized Design: The Anatomy of Success” in the October 2016 issue of MPO. If the team is chosen, then selecting the right project leader can be the key to success.

It’s easy to underestimate the need for project leadership when funding is tight. However, complexity should drive the decision to hire a project leader, not cost. Often, inexperience can lead to hiring individual consultants while foregoing a project leader or systems engineer. Even though this helps move feasibility along, it does little for the commercial design. Later, the device often requires redesign because vital details were not considered in the beginning.

One of the classic tools of project management is a project plan in the form of a Gantt chart. While this is an excellent tool to establish a high-level schedule and track due dates and critical path, it’s not very effective for tracking progress. One reason for this is that design and development doesn’t follow a waterfall or sequential process—it follows an iterative one. Another reason is that it’s difficult to correlate a team member’s estimate of percent complete with the actual time required to finish. Estimating is typically not a strong engineering attribute.

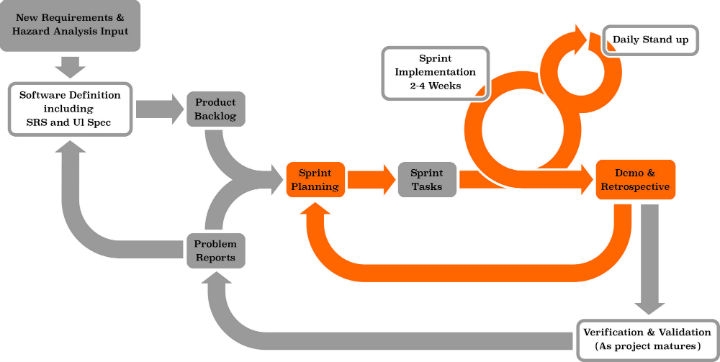

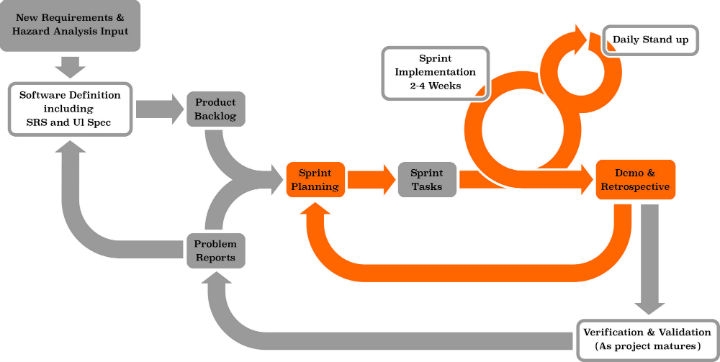

Agile Scrum is a helpful process to track progress more effectively than utilizing a project plan. It provides a framework to lead a team without micromanaging. Project plans help layout the overall strategy, while Scrum provides day-to-day tactics to move a project forward. Because of the transparency Scrum provides, trust is essential. When used in the right way, Scrum can empower the team and provide a leadership platform. When used incorrectly, the process falls apart.

The Scrum process provides day-to-day tactics to move a project forward.

Communication, Communication, Communication!

Most projects fall on hard times when expectations aren’t managed, vital details are miscommunicated, or each side is operating on different assumptions. Whenever engineering is outsourced, there is a great opportunity for communication to impact the end result (good or bad). It’s essential, therefore, that a strong bridge is created between the client technical lead and the project lead of the engineering firm, and they stay engaged throughout the project on both the business and technical aspects.

A technical background is important for a project leader to understand and manage a complex design project. He or she is responsible for the scope of a project and ensuring the output of the effort is on track, but, most importantly, not dictating how the team solves technical challenges. Project leaders must have the acumen to review and approve technical aspects of an evolving project. This also includes understanding that different expertise and focus are required at different times, with varying degrees of intensity and involvement.

In the beginning of a project, there’s a need for design control inputs such as product requirements. Here, the project leader benefits tremendously by receiving more than just the numbers. They need context, which includes information on the product, the requirements, and the reasoning behind these requirements in order to do an effective job. Other areas that provide important context are how the device will be used, how it should look, and what hazards may be encountered during normal and unexpected use. During this initial stage of design, close daily interaction and coordination between the project leads can make the difference between delivering the right product or a fancy paperweight.

Afterward, the service provider’s project leader needs to digest the technical information with its context and feedback for a systems and process perspective on the design. If the team is building a design that doesn’t match up with the client’s vision, the engineering project leader needs to push back and ensure both parties are synchronized. This can also be a time for brainstorming various technologies to incorporate into concepts to replace suboptimal approaches. Either way, it’s important for the client to be highly engaged at this point, so the right specifications are converted into testable requirements that ultimately come together in a viable product.

As the project moves into later phases, it benefits both parties to have the client step back to some extent and allow the engineering team to work unfettered. Unfortunately, it’s natural to carry the early close coordination into the development phase of a project, but here is where the team needs more guidance and clarification, and less direction. Setting task priorities in this stage can help keep a project on track.

At this point, a client project leader should provide priorities for the team and allow the team to do what they do best. The important communication that occurs in this phase is oriented toward the status of the team in meeting the goals of the project—not the technical details of requirements and design. This is an important time for the team to focus on priorities, reduce technical risk, and move the design forward. It’s also important for a project leader to be able to focus the team.

Charles Landers, former chief of helicopter design on the Apache, the attack helicopter of choice for the U.S. military, is an outspoken proponent for weight management: “Of primary importance to low product weight…is that low weight enables and enhances other desirable features. Certainly, low weight results in improved performance; higher speed, better climb, greater range, lowered component wear and tear. Low weight reduces power requirements with accompanying lowered fuel burn and resulting endurance, range, and operating cost improvement. Lowered power requirements result in longer engine life, reduced helicopter drive system wear and tear…The key advantage of weight management versus later weight reduction is the ability to react to inappropriate features and concepts at early phases of the design process…”

By concentrating on weight management, Landers is able to focus his team on superior helicopter design. Better yet, he creates a vantage point from which to dismiss poor design ideas. Different project leaders will find different focal points advantageous. On one project, the cost of goods was the focal point because final product cost could make or break the client’s business model. On another, a “rat hole” jar was the focus, requiring a monetary contribution every time a team member’s suggestion side-tracked progress.

A vexing issue that comes up in every product development is knowing when to quit—when do you call a product design “done”? Sometimes, it’s the client company that must rid themselves of the idea of a “perfect product” with all the bells and whistles. Sometimes, the engineering group won’t let go of a design unless they are comfortable with it, even after several iterations.

This is where close collaboration early in the project can really pay off. If both the client and service provider are aligned closely on product requirements, the more likely they are to arrive at a good definition of “done.” In addition, if the team has been focusing on high priority tasks, then the low priorities should be all that remain in the end. These could be pushed into a next software version or generation system. There is always room for improvement, but work also has to stop at some point.

In “License to Lead,” Ross Buchanan lists the top three things that employees are looking for from their managers: inclusion (which builds a strong sense of commitment), appreciation (which provides motivation), and accountability (for them and their colleagues based on clearly defined expectations).

David Rohlander writes in his book, “The CEO Code” that “The job of the leader is to create an environment where people will motivate themselves. To create such an environment, respect the individual, and believe in them. Great leaders believe in their team more than their team members believe in themselves.”

If a project leader can inspire and lead a team, the team members become more engaged and effective. This helps avoid some of the classic pitfalls of top-down project management. Project leadership for complex medical development involves a certain amount of technical expertise, an iterative process that enables and focuses the team, trust and respect of the team, courage, capability, conviction, emotional intelligence, and communication. As one moves from project management to leadership, the team will be more empowered, motivated, and involved. When done correctly, leading a team is more rewarding, managing the team becomes easier, and team members are more engaged.

Steve Maylish has been part of the medical device community for more than 30 years. He is currently chief commercial officer for Fusion Biotec, an Irvine, Calif.-based contract engineering firm that brings together art, science, and engineering to create medical devices. Early in his career, Maylish held positions at Fortune 100 corporations such as Johnson & Johnson, Shiley, Sorin Group, Baxter Healthcare, and Edwards Lifesciences.

Dave Mock is a project leader with Fusion Biotec. With degrees in engineering and business, Dave has more than 25 years of experience as a product development and manufacturing operations expert in the medical device industry. Dave received a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering and a Masters in Business Administration (MBA) from California State University, Fullerton.

In recent years, however, companies are realizing successful projects have more to do with the leadership skills—rather than the management skills—of the project manager. Much has been written about how to become a great leader and whether it comes naturally or can be learned through practice. It’s worth discussing the important qualities of a great project leader, but it can be even more valuable to highlight tools and methods that actually help develop and guide a team toward a leadership structure, rather than management.

Jeff Blanton writes in his book “Doing the Difficult—Boldly Leading Significant Change” that there are three C’s to project success: courage to inspire the team, capability to lead the team, and conviction to be successful.

In the book titled “Helping People Win at Work” by Ken Blanchard and Garry Ridge, the latter writes: “My leadership point of view is driven by my determination to make a difference, do worthwhile work, get good results, and, at the same time, have fun.”

If the team already trusts and respects the project manager, providing project leadership is not a large leap. Project leadership is a more nuanced process, but not necessarily more work.

Project leaders need soft skills in addition to leadership qualities. Most important is emotional intelligence, which encompasses self-awareness, self-regulation, social skills, empathy, and motivation. These traits enable a project leader to navigate team and stakeholder dynamics. Knowing one’s emotions, strengths, weaknesses, values, and goals and their impact on others, as well as controlling or redirecting disruptive emotions, moving team members toward a shared goal, considering other’s feelings, and being driven to reach goals for the sake of achievement—these encapsulate emotional intelligence.

Project leaders also need the ability to see the big picture, put the various stakeholders’ needs in context, negotiate and compromise, and collaborate with the team. The project leader must build trust and instill confidence in themselves and the team’s abilities. An early win on a project starts it off on a positive note and goes a long way to build confidence.

On the process side, technical project management is needed on both sides of the equation. But be careful, over-management can demoralize a team, while under-management can create a state of confusion. If the process of assembling a team or outsourcing is beginning, read my article titled “Specialized Design: The Anatomy of Success” in the October 2016 issue of MPO. If the team is chosen, then selecting the right project leader can be the key to success.

It’s easy to underestimate the need for project leadership when funding is tight. However, complexity should drive the decision to hire a project leader, not cost. Often, inexperience can lead to hiring individual consultants while foregoing a project leader or systems engineer. Even though this helps move feasibility along, it does little for the commercial design. Later, the device often requires redesign because vital details were not considered in the beginning.

One of the classic tools of project management is a project plan in the form of a Gantt chart. While this is an excellent tool to establish a high-level schedule and track due dates and critical path, it’s not very effective for tracking progress. One reason for this is that design and development doesn’t follow a waterfall or sequential process—it follows an iterative one. Another reason is that it’s difficult to correlate a team member’s estimate of percent complete with the actual time required to finish. Estimating is typically not a strong engineering attribute.

Agile Scrum is a helpful process to track progress more effectively than utilizing a project plan. It provides a framework to lead a team without micromanaging. Project plans help layout the overall strategy, while Scrum provides day-to-day tactics to move a project forward. Because of the transparency Scrum provides, trust is essential. When used in the right way, Scrum can empower the team and provide a leadership platform. When used incorrectly, the process falls apart.

The Scrum process provides day-to-day tactics to move a project forward.

Communication, Communication, Communication!

Most projects fall on hard times when expectations aren’t managed, vital details are miscommunicated, or each side is operating on different assumptions. Whenever engineering is outsourced, there is a great opportunity for communication to impact the end result (good or bad). It’s essential, therefore, that a strong bridge is created between the client technical lead and the project lead of the engineering firm, and they stay engaged throughout the project on both the business and technical aspects.

A technical background is important for a project leader to understand and manage a complex design project. He or she is responsible for the scope of a project and ensuring the output of the effort is on track, but, most importantly, not dictating how the team solves technical challenges. Project leaders must have the acumen to review and approve technical aspects of an evolving project. This also includes understanding that different expertise and focus are required at different times, with varying degrees of intensity and involvement.

In the beginning of a project, there’s a need for design control inputs such as product requirements. Here, the project leader benefits tremendously by receiving more than just the numbers. They need context, which includes information on the product, the requirements, and the reasoning behind these requirements in order to do an effective job. Other areas that provide important context are how the device will be used, how it should look, and what hazards may be encountered during normal and unexpected use. During this initial stage of design, close daily interaction and coordination between the project leads can make the difference between delivering the right product or a fancy paperweight.

Afterward, the service provider’s project leader needs to digest the technical information with its context and feedback for a systems and process perspective on the design. If the team is building a design that doesn’t match up with the client’s vision, the engineering project leader needs to push back and ensure both parties are synchronized. This can also be a time for brainstorming various technologies to incorporate into concepts to replace suboptimal approaches. Either way, it’s important for the client to be highly engaged at this point, so the right specifications are converted into testable requirements that ultimately come together in a viable product.

As the project moves into later phases, it benefits both parties to have the client step back to some extent and allow the engineering team to work unfettered. Unfortunately, it’s natural to carry the early close coordination into the development phase of a project, but here is where the team needs more guidance and clarification, and less direction. Setting task priorities in this stage can help keep a project on track.

At this point, a client project leader should provide priorities for the team and allow the team to do what they do best. The important communication that occurs in this phase is oriented toward the status of the team in meeting the goals of the project—not the technical details of requirements and design. This is an important time for the team to focus on priorities, reduce technical risk, and move the design forward. It’s also important for a project leader to be able to focus the team.

Charles Landers, former chief of helicopter design on the Apache, the attack helicopter of choice for the U.S. military, is an outspoken proponent for weight management: “Of primary importance to low product weight…is that low weight enables and enhances other desirable features. Certainly, low weight results in improved performance; higher speed, better climb, greater range, lowered component wear and tear. Low weight reduces power requirements with accompanying lowered fuel burn and resulting endurance, range, and operating cost improvement. Lowered power requirements result in longer engine life, reduced helicopter drive system wear and tear…The key advantage of weight management versus later weight reduction is the ability to react to inappropriate features and concepts at early phases of the design process…”

By concentrating on weight management, Landers is able to focus his team on superior helicopter design. Better yet, he creates a vantage point from which to dismiss poor design ideas. Different project leaders will find different focal points advantageous. On one project, the cost of goods was the focal point because final product cost could make or break the client’s business model. On another, a “rat hole” jar was the focus, requiring a monetary contribution every time a team member’s suggestion side-tracked progress.

A vexing issue that comes up in every product development is knowing when to quit—when do you call a product design “done”? Sometimes, it’s the client company that must rid themselves of the idea of a “perfect product” with all the bells and whistles. Sometimes, the engineering group won’t let go of a design unless they are comfortable with it, even after several iterations.

This is where close collaboration early in the project can really pay off. If both the client and service provider are aligned closely on product requirements, the more likely they are to arrive at a good definition of “done.” In addition, if the team has been focusing on high priority tasks, then the low priorities should be all that remain in the end. These could be pushed into a next software version or generation system. There is always room for improvement, but work also has to stop at some point.

In “License to Lead,” Ross Buchanan lists the top three things that employees are looking for from their managers: inclusion (which builds a strong sense of commitment), appreciation (which provides motivation), and accountability (for them and their colleagues based on clearly defined expectations).

David Rohlander writes in his book, “The CEO Code” that “The job of the leader is to create an environment where people will motivate themselves. To create such an environment, respect the individual, and believe in them. Great leaders believe in their team more than their team members believe in themselves.”

If a project leader can inspire and lead a team, the team members become more engaged and effective. This helps avoid some of the classic pitfalls of top-down project management. Project leadership for complex medical development involves a certain amount of technical expertise, an iterative process that enables and focuses the team, trust and respect of the team, courage, capability, conviction, emotional intelligence, and communication. As one moves from project management to leadership, the team will be more empowered, motivated, and involved. When done correctly, leading a team is more rewarding, managing the team becomes easier, and team members are more engaged.

Steve Maylish has been part of the medical device community for more than 30 years. He is currently chief commercial officer for Fusion Biotec, an Irvine, Calif.-based contract engineering firm that brings together art, science, and engineering to create medical devices. Early in his career, Maylish held positions at Fortune 100 corporations such as Johnson & Johnson, Shiley, Sorin Group, Baxter Healthcare, and Edwards Lifesciences.

Dave Mock is a project leader with Fusion Biotec. With degrees in engineering and business, Dave has more than 25 years of experience as a product development and manufacturing operations expert in the medical device industry. Dave received a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering and a Masters in Business Administration (MBA) from California State University, Fullerton.