Tomas Kellner, GE Reports06.26.18

GE announced major changes to its business portfolio designed to stimulate growth and generate more value for shareholders. GE’s Aviation, Power and Renewable Energy units will form a new core of the company. GE plans to turn GE Healthcare into a standalone business, distributing 80 percent to GE shareholders and monetizing the remaining 20 percent.

The company also plans to “fully separate” Baker Hughes, a GE company (BHGE), the tier-one oil and gas servicing and equipment player formed by the combination of GE Oil & Gas and Baker Hughes in 2017. The separation will take place “over the next two to three years,” according to GE. GE currently holds a 62.5 percent stake in BHGE valued at $23 billion.

In May, GE laid out plans to combine its Transportation business that makes locomotives and other railroad equipment with Wabtec Corporation in a deal valued at $11.1 billion.

GE also announced actions to strengthen its balance sheet, outlining “a clear path” to reducing its net debt by approximately $25 billion and “further de-risking GE Capital.” Finally, it offered some more details on its new operating philosophy, sharing how this structure will shift the center of gravity from to the businesses and generate at least $500 million in corporate savings by the end of 2020.

“Today marks an important milestone in GE’s history,” said GE Chairman and CEO John Flannery. “We are aggressively driving forward as an aviation, power and renewable energy company—three highly complementary businesses poised for future growth. We will continue to improve our operations and balance sheet as we make GE simpler and stronger.”

The company said it expected to maintain its current quarterly dividend, subject to board approval, until GE Healthcare becomes an independent entity. At that time, GE expects to adjust its dividend “in line with industrial peers,” according to GE. The new GE Healthcare board of directors will determine its dividend policy.

Flannery said that separating GE Healthcare and BHGE will allow them to invest in innovation and pursue their own growth strategies. “Today’s actions unlock both a pure-play healthcare company and a tier-one oil and gas services player,” Flannery said. “We are confident that positioning GE Healthcare and BHGE outside of GE’s current structure is best not only for GE and its owners, but also for these businesses, which will be able to strengthen their market leading positions and enhance their ability to invest for the future,” he added.

GE Healthcare recorded $3.5 billion operating profit on revenues of $19 billion in 2017. The company makes medical imaging scanners and other healthcare tools and equipment, including software, data analytics and AI applications.

It remains on the cutting edge of medicine. Its Life Sciences, unit, for example, is manufacturing equipment and tools pharmaceuticals companies use to make biologics, the world’s fastest-growing class of medicines, which represent eight out of the top 10 therapeutics on the market today. Its technology is also helping implement groundbreaking treatments like CAR-T cell therapy, that allows doctors to reengineer a patient’s immune system and turn it on their cancer, for example. “GE Healthcare’s vision is to drive more individualized, precise and effective patient outcomes,” said Kieran Murphy, president and CEO of GE Healthcare. “As an independent global healthcare business, we will have flexibility to pursue future growth opportunities, react quickly to changes in the industry and invest in innovation.”

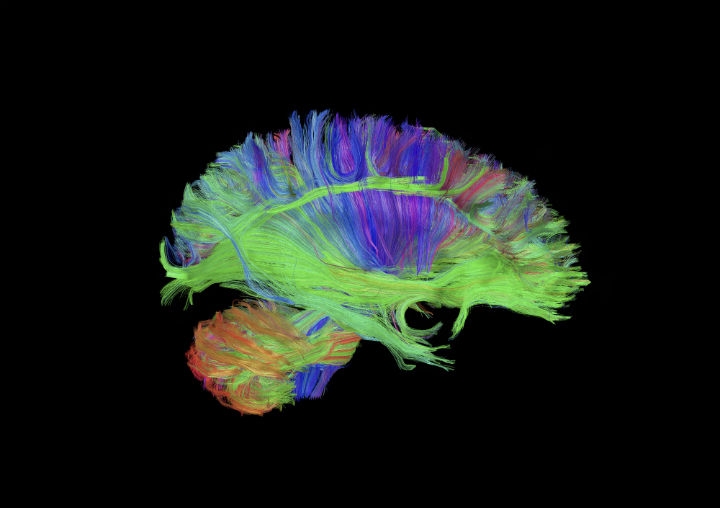

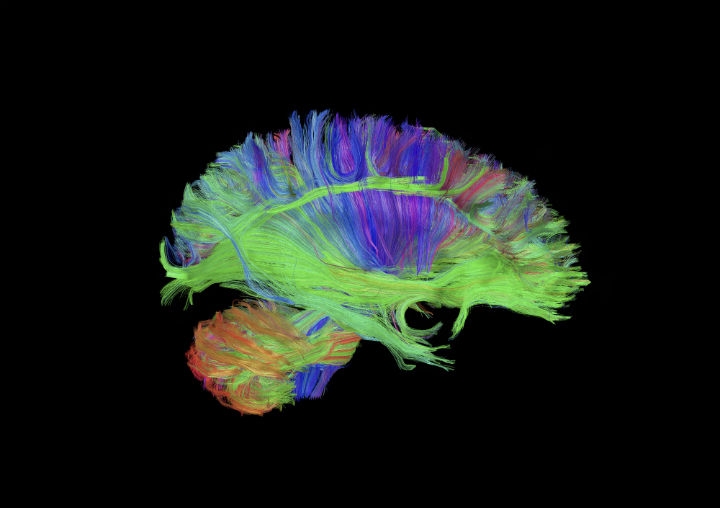

GE entered the medical imaging and healthcare business soon after it was formed in 1892. In 1896, just a year after Wilhelm Roentgen announced the discovery of X-rays, Elihu Thomson, the American engineer who co-founded GE with Thomas Edison, built a commercial X-ray machine “for diagnosing bone structures and locating foreign objects in the body.” Next, GE scientist William Coolidge invented the modern X-ray tube and built a portable X-ray machine used in military hospitals during World War I. He also invented the rotating Coolidge X-ray tube, a design that still powers many X-ray and computed tomography systems in the world today. His colleague Irving Langmuir, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932, patented a device called image intensifier. Such technology later allowed doctors to start lowering the radiation doze needed to image patients. The work of Ivar Giaever, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973 for his research of superconductivity, helped GE build first superconductive magnets and start making MRI machines. In the 1980s, John Schenck at GE Global Research took the first MRI image of the brain with a GE scanner.

An MRI image of the brain taken by a GE scanner. Image courtesy of GE Global Research.

GE of the Future

Flannery said that focusing GE on the aviation and power industries will make the company more focused and easier for investors to follow and measure. In fact, GE’s Aviation and Power businesses have been closely linked for more than a century. A gas turbine is, in many ways, similar to a jet engine and the two businesses units share a lot of technologies, including the use of the latest composite materials, 3D printing, and design features and know-how. It was a GE gas turbine engineer Sanford Moss who launched the company into the aviation business in 1917 when he designed a device called “turbosupercharger” that allowed plane engines to retain their horsepower at high altitudes. He later joined the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

The knowledge sharing also works in reverse. Today, GE Power’s advanced HA gas turbines, working inside two of the world’s most efficient combined-cycle power plants, utilize features originally developed by GE Aviation engineers for supersonic jet engines. Engineers move freely between the businesses, working closely to harness new manufacturing technologies like 3D printing. Jaroslaw Weronko, for example, helped design 3D printed parts for the GE Catalyst, a new aircraft engine with large sections printed from metal alloys. But he also spent time working on gas turbines at GE Power’s factory in Greenville, South Carolina. He said that such collaboration “makes you and everyone else stronger. Designing the GE Catalyst in less than two years was a sprint. If I didn’t have a chance to practice and learn from others, I would not have succeeded,” Weronko said.

GE’s Power and Aviation businesses are also working closely with scientists at GE Global Research. One of them, Krishan Luthra, spent two decades developing a wonder material called ceramic matrix composite. It is one-third the weight of metal and can withstand temperatures approaching 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit, where even the most advanced metal alloys grow soft. Operating at higher temperatures allows jet engines and turbines to extract more power from fuel and operate more efficiently. GE designed parts from the material for the HA turbines, as well as for the world’s largest jet engine, the GE9X and the LEAP, developed by CFM International, a 50-50 joint-venture between GE Aviation and Safran Aircraft Engines. The LEAP has brought in more than $200 billion in engine orders at U.S. list price.

GE built the first jet engine in the U.S. Today GE technology powers two out of every three commercial airliner departures around the world, and GE Aviation’s installed base includes more than 65,000 engines. Machines made by GE Power have the capacity to generate more a third of the world’s electricity, and the business unit has some 7,000 gas turbines in the field.

Onshore wind turbines from GE Renewable Energy installed around the world have the capacity to generate 60,000 megawatts, enough to supply all of Indonesia. The business unit is also developing the Haliade-X, the world’s largest offshore wind turbine. Just one of these 12-megawatt turbines will be capable of powering the equivalent of 16,000 European homes.

GE Aviation recorded $5.4 billion operating profit on revenues of $27 billion in 2017, and the unit has a $200 billion backlog. GE Power reported revenues of $35 billion and operating profit of $1.9 billion. The business has a $98 billion backlog. GE Renewable Energy brought in $9 billion in revenues and $600 million in operating profit. Its backlog stands at $15 billion.

GE will also keep its innovation engine, GE Global Research. It will help GE businesses develop new products and technologies. But the company is planning to open the facility to outside partners and help them solve tough engineering problems and accelerate new technologies. The team will report to David Joyce, GE Aviation CEO and GE Vice Chair, who helped GE roll out businesses like GE Additive, focusing on 3D printing technologies.

Flannery said that the changes will make the company “simpler and stronger,” and accelerate growth across its businesses. “I’m confident that today’s actions, in conjunction with other changes we have already made, will produce improved operating results going forward,” he said. “We are focused on executing the strategy and implementing the structure we’ve laid out today to position our businesses for future growth.”

This article originally appeared in GE Reports.

The company also plans to “fully separate” Baker Hughes, a GE company (BHGE), the tier-one oil and gas servicing and equipment player formed by the combination of GE Oil & Gas and Baker Hughes in 2017. The separation will take place “over the next two to three years,” according to GE. GE currently holds a 62.5 percent stake in BHGE valued at $23 billion.

In May, GE laid out plans to combine its Transportation business that makes locomotives and other railroad equipment with Wabtec Corporation in a deal valued at $11.1 billion.

GE also announced actions to strengthen its balance sheet, outlining “a clear path” to reducing its net debt by approximately $25 billion and “further de-risking GE Capital.” Finally, it offered some more details on its new operating philosophy, sharing how this structure will shift the center of gravity from to the businesses and generate at least $500 million in corporate savings by the end of 2020.

“Today marks an important milestone in GE’s history,” said GE Chairman and CEO John Flannery. “We are aggressively driving forward as an aviation, power and renewable energy company—three highly complementary businesses poised for future growth. We will continue to improve our operations and balance sheet as we make GE simpler and stronger.”

The company said it expected to maintain its current quarterly dividend, subject to board approval, until GE Healthcare becomes an independent entity. At that time, GE expects to adjust its dividend “in line with industrial peers,” according to GE. The new GE Healthcare board of directors will determine its dividend policy.

Flannery said that separating GE Healthcare and BHGE will allow them to invest in innovation and pursue their own growth strategies. “Today’s actions unlock both a pure-play healthcare company and a tier-one oil and gas services player,” Flannery said. “We are confident that positioning GE Healthcare and BHGE outside of GE’s current structure is best not only for GE and its owners, but also for these businesses, which will be able to strengthen their market leading positions and enhance their ability to invest for the future,” he added.

GE Healthcare recorded $3.5 billion operating profit on revenues of $19 billion in 2017. The company makes medical imaging scanners and other healthcare tools and equipment, including software, data analytics and AI applications.

It remains on the cutting edge of medicine. Its Life Sciences, unit, for example, is manufacturing equipment and tools pharmaceuticals companies use to make biologics, the world’s fastest-growing class of medicines, which represent eight out of the top 10 therapeutics on the market today. Its technology is also helping implement groundbreaking treatments like CAR-T cell therapy, that allows doctors to reengineer a patient’s immune system and turn it on their cancer, for example. “GE Healthcare’s vision is to drive more individualized, precise and effective patient outcomes,” said Kieran Murphy, president and CEO of GE Healthcare. “As an independent global healthcare business, we will have flexibility to pursue future growth opportunities, react quickly to changes in the industry and invest in innovation.”

GE entered the medical imaging and healthcare business soon after it was formed in 1892. In 1896, just a year after Wilhelm Roentgen announced the discovery of X-rays, Elihu Thomson, the American engineer who co-founded GE with Thomas Edison, built a commercial X-ray machine “for diagnosing bone structures and locating foreign objects in the body.” Next, GE scientist William Coolidge invented the modern X-ray tube and built a portable X-ray machine used in military hospitals during World War I. He also invented the rotating Coolidge X-ray tube, a design that still powers many X-ray and computed tomography systems in the world today. His colleague Irving Langmuir, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932, patented a device called image intensifier. Such technology later allowed doctors to start lowering the radiation doze needed to image patients. The work of Ivar Giaever, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973 for his research of superconductivity, helped GE build first superconductive magnets and start making MRI machines. In the 1980s, John Schenck at GE Global Research took the first MRI image of the brain with a GE scanner.

An MRI image of the brain taken by a GE scanner. Image courtesy of GE Global Research.

GE of the Future

Flannery said that focusing GE on the aviation and power industries will make the company more focused and easier for investors to follow and measure. In fact, GE’s Aviation and Power businesses have been closely linked for more than a century. A gas turbine is, in many ways, similar to a jet engine and the two businesses units share a lot of technologies, including the use of the latest composite materials, 3D printing, and design features and know-how. It was a GE gas turbine engineer Sanford Moss who launched the company into the aviation business in 1917 when he designed a device called “turbosupercharger” that allowed plane engines to retain their horsepower at high altitudes. He later joined the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

The knowledge sharing also works in reverse. Today, GE Power’s advanced HA gas turbines, working inside two of the world’s most efficient combined-cycle power plants, utilize features originally developed by GE Aviation engineers for supersonic jet engines. Engineers move freely between the businesses, working closely to harness new manufacturing technologies like 3D printing. Jaroslaw Weronko, for example, helped design 3D printed parts for the GE Catalyst, a new aircraft engine with large sections printed from metal alloys. But he also spent time working on gas turbines at GE Power’s factory in Greenville, South Carolina. He said that such collaboration “makes you and everyone else stronger. Designing the GE Catalyst in less than two years was a sprint. If I didn’t have a chance to practice and learn from others, I would not have succeeded,” Weronko said.

GE’s Power and Aviation businesses are also working closely with scientists at GE Global Research. One of them, Krishan Luthra, spent two decades developing a wonder material called ceramic matrix composite. It is one-third the weight of metal and can withstand temperatures approaching 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit, where even the most advanced metal alloys grow soft. Operating at higher temperatures allows jet engines and turbines to extract more power from fuel and operate more efficiently. GE designed parts from the material for the HA turbines, as well as for the world’s largest jet engine, the GE9X and the LEAP, developed by CFM International, a 50-50 joint-venture between GE Aviation and Safran Aircraft Engines. The LEAP has brought in more than $200 billion in engine orders at U.S. list price.

GE built the first jet engine in the U.S. Today GE technology powers two out of every three commercial airliner departures around the world, and GE Aviation’s installed base includes more than 65,000 engines. Machines made by GE Power have the capacity to generate more a third of the world’s electricity, and the business unit has some 7,000 gas turbines in the field.

Onshore wind turbines from GE Renewable Energy installed around the world have the capacity to generate 60,000 megawatts, enough to supply all of Indonesia. The business unit is also developing the Haliade-X, the world’s largest offshore wind turbine. Just one of these 12-megawatt turbines will be capable of powering the equivalent of 16,000 European homes.

GE Aviation recorded $5.4 billion operating profit on revenues of $27 billion in 2017, and the unit has a $200 billion backlog. GE Power reported revenues of $35 billion and operating profit of $1.9 billion. The business has a $98 billion backlog. GE Renewable Energy brought in $9 billion in revenues and $600 million in operating profit. Its backlog stands at $15 billion.

GE will also keep its innovation engine, GE Global Research. It will help GE businesses develop new products and technologies. But the company is planning to open the facility to outside partners and help them solve tough engineering problems and accelerate new technologies. The team will report to David Joyce, GE Aviation CEO and GE Vice Chair, who helped GE roll out businesses like GE Additive, focusing on 3D printing technologies.

Flannery said that the changes will make the company “simpler and stronger,” and accelerate growth across its businesses. “I’m confident that today’s actions, in conjunction with other changes we have already made, will produce improved operating results going forward,” he said. “We are focused on executing the strategy and implementing the structure we’ve laid out today to position our businesses for future growth.”

This article originally appeared in GE Reports.