P.D. Olson, GE Reports05.31.17

Tammy Woodhams was desperate to get back to her job at the National Criminal Justice Association in Washington, D.C. But there was a problem. Part of her face and neck had swollen up so much that she was almost unrecognizable, and it was difficult for her to move and talk.

Woodhams was suffering from lymphedema, a side effect of the treatment she’d received for tongue and tonsil cancer. Lymph nodes are the little bean-like glands in our necks, armpits and elsewhere that filter out pathogens, dead cells and other waste from the lymph fluid and help the body stage an immune response. When they get damaged, which can happen during radiation therapy or lymph node dissection, the result is lymphedema, an incurable condition that causes arms, legs and faces to fill with fluid and swell to sometimes elephantine proportions. “I was told that I would probably never eat out in public another day in my life,” Woodhams remembered. “I was told that I should apply for Social Security benefits right away, because I wouldn’t be working anymore. I was terrified.”

Then Kathy Konosky, an occupational therapist Woodhams was working with a few years ago at the University of Michigan, mentioned she’d just learned about a new device that she wanted to try out on Woodhams.

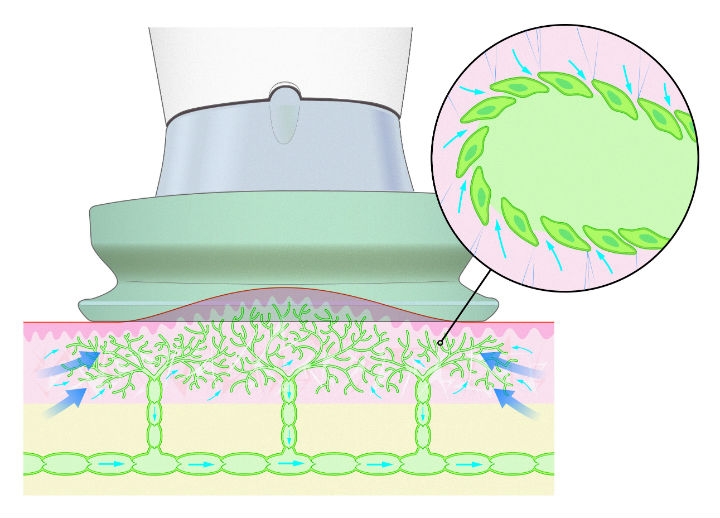

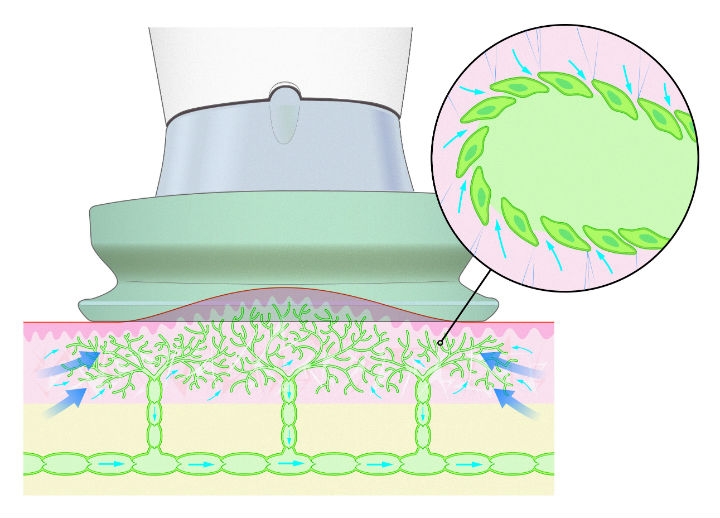

The gadget was called PhysioTouch. Designed and built by Finnish company HLD Healthy Life Devices, the hand-held machine works on a principle that’s similar to cupping, a form of alternative medicine used to treat inflammation and other conditions. Traditional cupping works by lighting a match inside a glass cup and then quickly applying the warmed cup to the patient’s skin. As the air inside the cup cools down, it creates a vacuum that pulls on the skin. With PhysioTouch, a small vacuum lifts the skin to activate the clogged capillaries that are retaining fluid. As they start to unclog, fluid moves around the body more freely and the swelling goes down. Unlike cupping, where pressures can be high enough to cause bruising, PhysioTouch electronically generates precisely controlled, benign pressure. It also has a vibration feature that supports the treatment.

As capillaries start to unclog, fluid moves around the body more freely and the swelling goes down.

The technique is two to three times more effective than traditional massage for relieving the symptoms of lymphedema, according to a clinical study that Healthy Life Devices conducted on a small number of patients. “We get better results than manual therapy,” said its chief executive, Kalle Palomaki.

Palomaki, an experienced salesman, joined HLD as CEO in November 2013. His former business school classmate Tapani Taskinen had invented the PhysioTouch and filed the first patent for the device, which costs $5,000 and weighs 1.3 kilograms, in 2005.

But even with Palomaki on board, the startup needed some extra help. So in September 2015 Healthy Life Devices joined GE’s Health Innovation Village in Helsinki where over 40 healthcare startups have access to experts and managers from GE’s Healthcare division, as well as the company’s distributors. Being part of the village helped Palomaki grow the company by making crucial business connections with other health technology companies.

On one occasion, the global chief medical officer of GE Healthcare came and spent close to three hours listening to the village CEOs, says Palomaki. “In any other situation, having an audience with him would be pretty much impossible,” Palomaki said.

Right now Palomaki and his four employees are in the process of closing an early round of funding of under $10 million. It’ll help them hire their first sales representatives in the United States, the largest (and most promising) market for the PhysioTouch. Early response has been promising. He’s found that around 80 percent of therapists will buy the device after a 30-day trial. HLD’s customers include health-care organizations such as Johns Hopkins Hospital, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and the University of Michigan.

“We get better results than manual therapy,” said its chief executive, Kalle Palomaki.

For Woodhams, the device restored her ability to move and talk in a way that others could understand her. “There are probably people like me who are newly diagnosed, who have secondary lymphedema and don’t even know it,” she added. “This device … changed my life.”

This article originally appeared in GE Reports.

Woodhams was suffering from lymphedema, a side effect of the treatment she’d received for tongue and tonsil cancer. Lymph nodes are the little bean-like glands in our necks, armpits and elsewhere that filter out pathogens, dead cells and other waste from the lymph fluid and help the body stage an immune response. When they get damaged, which can happen during radiation therapy or lymph node dissection, the result is lymphedema, an incurable condition that causes arms, legs and faces to fill with fluid and swell to sometimes elephantine proportions. “I was told that I would probably never eat out in public another day in my life,” Woodhams remembered. “I was told that I should apply for Social Security benefits right away, because I wouldn’t be working anymore. I was terrified.”

Then Kathy Konosky, an occupational therapist Woodhams was working with a few years ago at the University of Michigan, mentioned she’d just learned about a new device that she wanted to try out on Woodhams.

The gadget was called PhysioTouch. Designed and built by Finnish company HLD Healthy Life Devices, the hand-held machine works on a principle that’s similar to cupping, a form of alternative medicine used to treat inflammation and other conditions. Traditional cupping works by lighting a match inside a glass cup and then quickly applying the warmed cup to the patient’s skin. As the air inside the cup cools down, it creates a vacuum that pulls on the skin. With PhysioTouch, a small vacuum lifts the skin to activate the clogged capillaries that are retaining fluid. As they start to unclog, fluid moves around the body more freely and the swelling goes down. Unlike cupping, where pressures can be high enough to cause bruising, PhysioTouch electronically generates precisely controlled, benign pressure. It also has a vibration feature that supports the treatment.

As capillaries start to unclog, fluid moves around the body more freely and the swelling goes down.

The technique is two to three times more effective than traditional massage for relieving the symptoms of lymphedema, according to a clinical study that Healthy Life Devices conducted on a small number of patients. “We get better results than manual therapy,” said its chief executive, Kalle Palomaki.

Palomaki, an experienced salesman, joined HLD as CEO in November 2013. His former business school classmate Tapani Taskinen had invented the PhysioTouch and filed the first patent for the device, which costs $5,000 and weighs 1.3 kilograms, in 2005.

But even with Palomaki on board, the startup needed some extra help. So in September 2015 Healthy Life Devices joined GE’s Health Innovation Village in Helsinki where over 40 healthcare startups have access to experts and managers from GE’s Healthcare division, as well as the company’s distributors. Being part of the village helped Palomaki grow the company by making crucial business connections with other health technology companies.

On one occasion, the global chief medical officer of GE Healthcare came and spent close to three hours listening to the village CEOs, says Palomaki. “In any other situation, having an audience with him would be pretty much impossible,” Palomaki said.

Right now Palomaki and his four employees are in the process of closing an early round of funding of under $10 million. It’ll help them hire their first sales representatives in the United States, the largest (and most promising) market for the PhysioTouch. Early response has been promising. He’s found that around 80 percent of therapists will buy the device after a 30-day trial. HLD’s customers include health-care organizations such as Johns Hopkins Hospital, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and the University of Michigan.

“We get better results than manual therapy,” said its chief executive, Kalle Palomaki.

For Woodhams, the device restored her ability to move and talk in a way that others could understand her. “There are probably people like me who are newly diagnosed, who have secondary lymphedema and don’t even know it,” she added. “This device … changed my life.”

This article originally appeared in GE Reports.