Mihir Torsekar, Director of the Global Trade Desk, Level International07.22.21

Sometimes a crisis can reveal the truth about a relationship. Take the U.S.-China medtech trading relationship before and after COVID-19 as an example. In the years leading up to the pandemic—which began in late 2019—geopolitical tensions between the two economies boiled over into a trade war, underscored by the application of tariffs on nearly $2 billion worth of U.S. medtech imports from China.

The tariffs were imposed at a time when the United States had increasingly begun sourcing these goods from its other leading suppliers, led by Mexico, Ireland, Germany, and Malaysia. This trend persisted up until 2019, when the pandemic took hold; China was the only main supplier from whom the United States reduced their imports of these goods from 2017-19.

In sharp contrast, during the 2019-20 pandemic, China leaped ahead of Ireland and Germany to become the United States’ second largest supplier of medical goods, behind Mexico. The two biggest drivers were the surge in demand for products associated with the COVID-19 emergency response and the years of steady U.S. investments into China’s medtech sector.

China’s Supplier Status

The pandemic has occasioned a drastic realignment of the United States’ leading medtech suppliers. After more than a decade as the United States’ fourth-largest supplier, China is now the United States’ second leading provider of these goods, trailing only Mexico.*

In the three years preceding the pandemic of 2019, U.S. imports of medical goods from Mexico, Ireland, Germany, and Malaysia all expanded by between 23 to 39 percent, but only grew by 11 percent from China. These numbers partially reflected the impact of the trade war—to be discussed in the next section—which began in 2018 and has continued throughout the pandemic period.

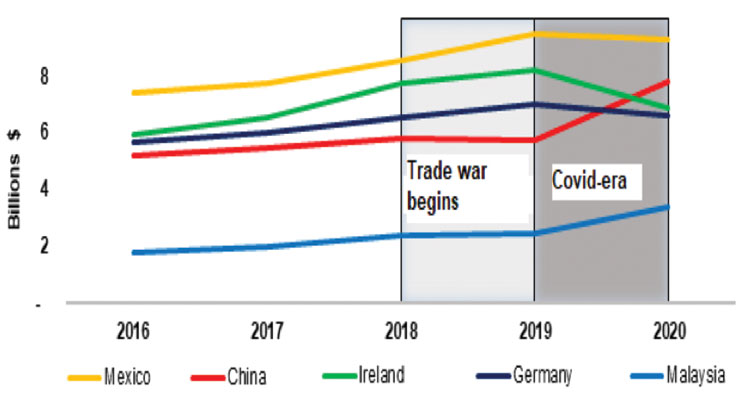

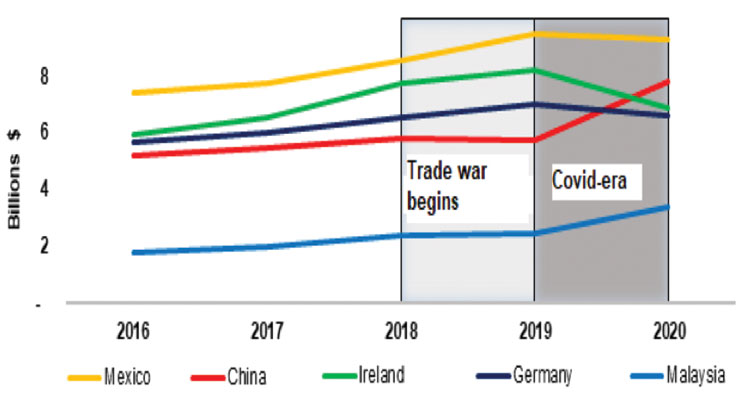

This trend has reversed during the pandemic period of 2019-20. During this period, U.S. imports of medical goods from China grew by 36 percent ($2 billion)—faster than with any of the other top five suppliers, three of whom registered declines (Figure 1). Moreover, nearly half ($3.5 billion) of the value of U.S. medtech imports from China grew by more than 100 percent.

Figure 1: U.S. imports of medical goods from its top five suppliers during 2016–20. (Source: Official Statistics of the U.S. Department of Commerce)

On the supply side, U.S. exports of medical goods to China have remained consistent over the past four to five years. However, the dramatic increase in these imports from China during the pandemic has translated into an increase in the bilateral trade deficit of medical goods of more than 170 percent ($1.9 billion). The United States has traditionally served as China’s largest supplier of medtech, with chemical reagents serving as the largest category of U.S. medtech exports.

COVID Demand Drives Imports

Unsurprisingly, much of the rebound in U.S. imports of medical goods from China can be accounted for by heightened demand for goods associated with the COVID-19 emergency response. The pandemic saw China emerge as the United States’ second leading supplier of these goods, behind Ireland. Moreover, by 2020, China had gone from representing 8 percent of the U.S. supply to 14 percent of the total. The vast majority of these imports were goods of low value, such as medical textiles and hospital supplies.

What About the Tariffs?

Almost three years ago to the date (July 6, 2018), the United States began assessing tariffs on goods from China in response to the findings of a 2017 investigation into China’s policies of forced technology transfer and intellectual property practices. These actions were unveiled in a series of product tranches that, by last year, covered about $1.8 billion worth of medical goods imports from China. China responded in turn, immediately applying tariffs on roughly 85 percent of the value of its sectoral U.S. imports at the time.

Initially at least, it appeared the tariffs produced the intended effect of reducing U.S. imports from China. However, this trade was mostly diverted to other suppliers; U.S. imports of the goods impacted by tariffs increased from each of its major suppliers, except for China during 2017–19. Over this period, China fell from being the United States’ fourth largest supplier of medical goods, on which tariffs were assessed, to its sixth.

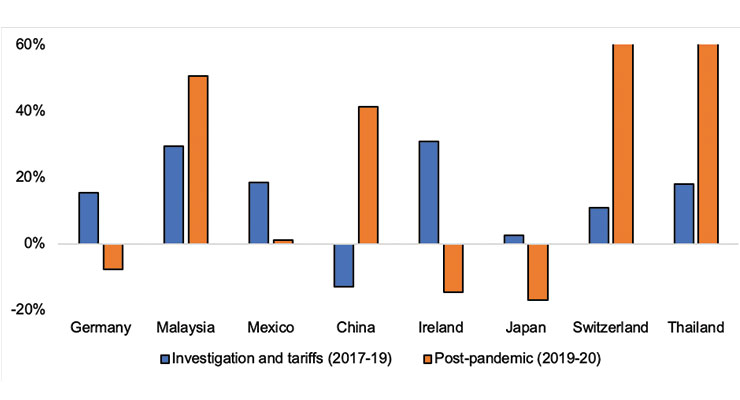

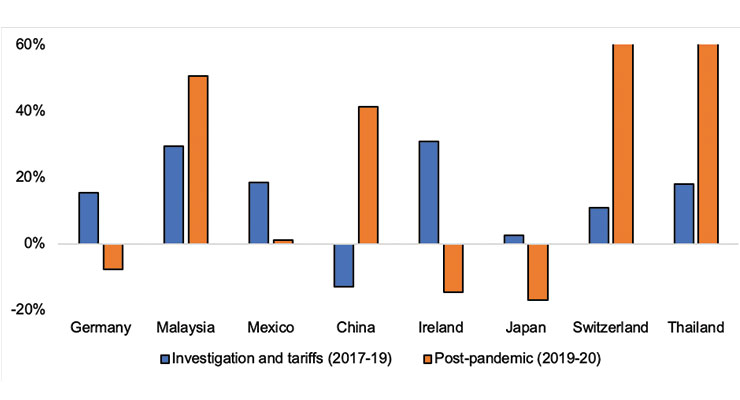

In sharp contrast, from 2019-20, U.S. imports of these goods from China rebounded by more than 40 percent and the country had returned to being the United States’ fourth-largest supplier by 2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: U.S. imports from its top eight suppliers for medical goods impacted by tariffs—2017-19, 2019-20. (Source: Official Statistics of the U.S. Department of Commerce)

U.S. Import Dependence Is Reflected in Foreign Direct Investment

The United States’ import dependence on China is largely reflected in the substantial foreign direct investments (FDI) that have been made into the country’s medtech sector by U.S. multinationals.

In the near decade preceding the pandemic, inbound greenfield investments (i.e. new projects that are undertaken by a parent company) from the United States into China’s medtech sector tallied roughly $550 million, trailing only Ireland’s $680 million, according to FDI intelligence.

For the United States, FDI into China has largely served two ends: 1) to provide relatively inexpensive inputs for U.S. firms from which could be imported back into the United States for final production and 2) to serve as a manufacturing location to supply the local market.

To the first point, the most recent data suggest the U.S. is reducing its reliance on China as a supplier of medtech inputs and is increasingly importing relatively higher-value-added goods. For example, related-party inputs—trade that is conducted between a parent corporation based in the U.S. and their Chinese affiliates—has declined by 11 percentage points to 28 ($141 million) between 2015-20. At the same time, the fastest growing U.S. medtech imports from China were therapeutic devices and diagnostic equipment, as opposed to goods of low value, such as hospital supplies and consumables.

To the second point, U.S. multinationals have flocked to China in an effort to supply the underdeveloped local market. These efforts have been undergirded by Chinese-government policies, which has welcomed investment by high-tech firms. These policy support measures range from customs clearance facilitation to tax cuts to reduced red tape to the recent removal of foreign ownership restrictions. In addition, improving intellectual property protection and a general climate of favorable business conditions have catapulted China from 78th to 31st place in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index between 2018-20.

Since the pandemic took hold, the Chinese government has continued to pursue policies aimed at attracting FDI into the medtech sector. For example, the PRC Foreign Investment Law, which came into effect in 2020, extends equal treatment to medical products made by foreign-funded enterprises to domestically produced ones, which could prove highly attractive to medtech firms seeking government procurement opportunities. Further, the Chinese government has permitted overseas clinical trial data to be submitted for the registration of devices in China and has supported the expedited approval of domestically produced Class III and imported Class II and III devices.

Moreover, the country’s latest five-year strategic plan, as well as the Shanghai municipal government’s work report for 2021 notes the emphasis being placed on “innovation-driven development” to facilitate the innovation and development of foreign-financed enterprises in China.

These policies may be translating into increased investment despite the pandemic. For example, according to the U.S.-China Investment Hub, FDI by U.S. companies into China’s Health, Pharmaceuticals, and Biotechnology reached an all-time peak of $3 billion during 2019, with the medtech sector attracting a significant proportion of the total in the form of greenfield investment.

Conclusion

The pandemic appears to have brought significant clarity to the centrality of China to the United States’ medtech supply chain. It appears in the short term, at least, policy measures intended to reduce this dependence—such as import tariffs on Chinese-produced medtech—have proven insufficient.

* Though not a focus of this article, Malaysia and Singapore also witnessed dramatic demand growth from the United States during the pandemic; both improved their rankings by three spots each.

Mihir Torsekar is the director of the Global Trade Desk at Level International. He has been publishing reports on trends impacting the global medtech industry for more than 10 years.

The tariffs were imposed at a time when the United States had increasingly begun sourcing these goods from its other leading suppliers, led by Mexico, Ireland, Germany, and Malaysia. This trend persisted up until 2019, when the pandemic took hold; China was the only main supplier from whom the United States reduced their imports of these goods from 2017-19.

In sharp contrast, during the 2019-20 pandemic, China leaped ahead of Ireland and Germany to become the United States’ second largest supplier of medical goods, behind Mexico. The two biggest drivers were the surge in demand for products associated with the COVID-19 emergency response and the years of steady U.S. investments into China’s medtech sector.

China’s Supplier Status

The pandemic has occasioned a drastic realignment of the United States’ leading medtech suppliers. After more than a decade as the United States’ fourth-largest supplier, China is now the United States’ second leading provider of these goods, trailing only Mexico.*

In the three years preceding the pandemic of 2019, U.S. imports of medical goods from Mexico, Ireland, Germany, and Malaysia all expanded by between 23 to 39 percent, but only grew by 11 percent from China. These numbers partially reflected the impact of the trade war—to be discussed in the next section—which began in 2018 and has continued throughout the pandemic period.

This trend has reversed during the pandemic period of 2019-20. During this period, U.S. imports of medical goods from China grew by 36 percent ($2 billion)—faster than with any of the other top five suppliers, three of whom registered declines (Figure 1). Moreover, nearly half ($3.5 billion) of the value of U.S. medtech imports from China grew by more than 100 percent.

Figure 1: U.S. imports of medical goods from its top five suppliers during 2016–20. (Source: Official Statistics of the U.S. Department of Commerce)

On the supply side, U.S. exports of medical goods to China have remained consistent over the past four to five years. However, the dramatic increase in these imports from China during the pandemic has translated into an increase in the bilateral trade deficit of medical goods of more than 170 percent ($1.9 billion). The United States has traditionally served as China’s largest supplier of medtech, with chemical reagents serving as the largest category of U.S. medtech exports.

COVID Demand Drives Imports

Unsurprisingly, much of the rebound in U.S. imports of medical goods from China can be accounted for by heightened demand for goods associated with the COVID-19 emergency response. The pandemic saw China emerge as the United States’ second leading supplier of these goods, behind Ireland. Moreover, by 2020, China had gone from representing 8 percent of the U.S. supply to 14 percent of the total. The vast majority of these imports were goods of low value, such as medical textiles and hospital supplies.

What About the Tariffs?

Almost three years ago to the date (July 6, 2018), the United States began assessing tariffs on goods from China in response to the findings of a 2017 investigation into China’s policies of forced technology transfer and intellectual property practices. These actions were unveiled in a series of product tranches that, by last year, covered about $1.8 billion worth of medical goods imports from China. China responded in turn, immediately applying tariffs on roughly 85 percent of the value of its sectoral U.S. imports at the time.

Initially at least, it appeared the tariffs produced the intended effect of reducing U.S. imports from China. However, this trade was mostly diverted to other suppliers; U.S. imports of the goods impacted by tariffs increased from each of its major suppliers, except for China during 2017–19. Over this period, China fell from being the United States’ fourth largest supplier of medical goods, on which tariffs were assessed, to its sixth.

In sharp contrast, from 2019-20, U.S. imports of these goods from China rebounded by more than 40 percent and the country had returned to being the United States’ fourth-largest supplier by 2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: U.S. imports from its top eight suppliers for medical goods impacted by tariffs—2017-19, 2019-20. (Source: Official Statistics of the U.S. Department of Commerce)

U.S. Import Dependence Is Reflected in Foreign Direct Investment

The United States’ import dependence on China is largely reflected in the substantial foreign direct investments (FDI) that have been made into the country’s medtech sector by U.S. multinationals.

In the near decade preceding the pandemic, inbound greenfield investments (i.e. new projects that are undertaken by a parent company) from the United States into China’s medtech sector tallied roughly $550 million, trailing only Ireland’s $680 million, according to FDI intelligence.

For the United States, FDI into China has largely served two ends: 1) to provide relatively inexpensive inputs for U.S. firms from which could be imported back into the United States for final production and 2) to serve as a manufacturing location to supply the local market.

To the first point, the most recent data suggest the U.S. is reducing its reliance on China as a supplier of medtech inputs and is increasingly importing relatively higher-value-added goods. For example, related-party inputs—trade that is conducted between a parent corporation based in the U.S. and their Chinese affiliates—has declined by 11 percentage points to 28 ($141 million) between 2015-20. At the same time, the fastest growing U.S. medtech imports from China were therapeutic devices and diagnostic equipment, as opposed to goods of low value, such as hospital supplies and consumables.

To the second point, U.S. multinationals have flocked to China in an effort to supply the underdeveloped local market. These efforts have been undergirded by Chinese-government policies, which has welcomed investment by high-tech firms. These policy support measures range from customs clearance facilitation to tax cuts to reduced red tape to the recent removal of foreign ownership restrictions. In addition, improving intellectual property protection and a general climate of favorable business conditions have catapulted China from 78th to 31st place in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index between 2018-20.

Since the pandemic took hold, the Chinese government has continued to pursue policies aimed at attracting FDI into the medtech sector. For example, the PRC Foreign Investment Law, which came into effect in 2020, extends equal treatment to medical products made by foreign-funded enterprises to domestically produced ones, which could prove highly attractive to medtech firms seeking government procurement opportunities. Further, the Chinese government has permitted overseas clinical trial data to be submitted for the registration of devices in China and has supported the expedited approval of domestically produced Class III and imported Class II and III devices.

Moreover, the country’s latest five-year strategic plan, as well as the Shanghai municipal government’s work report for 2021 notes the emphasis being placed on “innovation-driven development” to facilitate the innovation and development of foreign-financed enterprises in China.

These policies may be translating into increased investment despite the pandemic. For example, according to the U.S.-China Investment Hub, FDI by U.S. companies into China’s Health, Pharmaceuticals, and Biotechnology reached an all-time peak of $3 billion during 2019, with the medtech sector attracting a significant proportion of the total in the form of greenfield investment.

Conclusion

The pandemic appears to have brought significant clarity to the centrality of China to the United States’ medtech supply chain. It appears in the short term, at least, policy measures intended to reduce this dependence—such as import tariffs on Chinese-produced medtech—have proven insufficient.

* Though not a focus of this article, Malaysia and Singapore also witnessed dramatic demand growth from the United States during the pandemic; both improved their rankings by three spots each.

Mihir Torsekar is the director of the Global Trade Desk at Level International. He has been publishing reports on trends impacting the global medtech industry for more than 10 years.