Mihir Torsekar, Analyst, U.S. International Trade Commission04.03.19

Over the past two years, medical devices have been implicated in a volley of trade actions between the United States and China. To better understand the potential implications of these trade actions, this article first provides an overview of U.S-China medtech trade, discusses China’s importance as a principal destination for investment for U.S. industry, and concludes with a brief discussion of China’s domestic policies, which have appeared to play a role in effecting these tariffs.

Section 301 Tariffs Hit Medical Devices

On July 6, 2018, the United States announced tariffs of 25 percent on $34 billion worth of imports from China (818 products), with an additional $16 billion (284 products)1 unveiled on August 23. These measures were made in response to Section 301 investigations, which the United States initiated in August 2017 to determine the possible impact of China’s forced technology transfer and intellectual property practices on U.S. national security interests.

Medical devices and related parts factored prominently into these actions, representing about 6 percent ($2.7 billion) of the value of the tariffs currently being assessed. Further, dutiable medtech goods equated to nearly half of all U.S. medtech imports from China in 2017. China has since responded by applying 25 percent tariffs on medtech imports worth $4.7 billion—roughly 85 percent of its sectoral U.S. imports in 2017.

U.S.-China Trade Overview

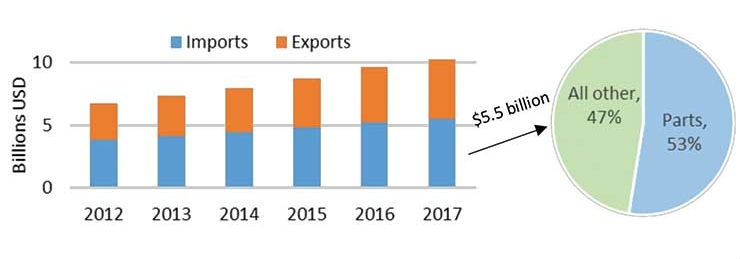

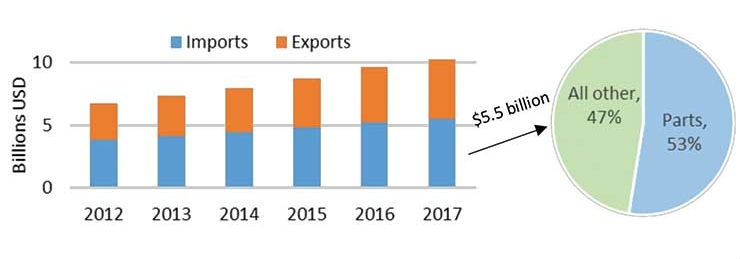

The United States is the world’s largest importer of medical technology and relies heavily on imports from China, its fourth largest supplier (after Mexico, Ireland, and Germany). The bilateral trade deficit between the United States and China for medtech has been growing slightly in recent years, reaching $711 million in 2017, driven principally by U.S. imports of Chinese-made parts and components (Figure 1). The goods for which the United States has maintained its highest trade deficits with China consist mostly of parts for devices such as X-ray machines and orthopedic implants as well as disposables like surgical gloves and bandages.

Figure 1: U.S. medical device imports, exports, and total trade with China, 2012–17 (left); 2017 U.S. medical device imports by parts and all other devices (right). Source: IHS Markit, Global Trade Atlas (accessed Feb. 21, 2019).

At the same time, the United States is China’s largest supplier of medical technology, accounting for close to one-third of that country’s $18.6 billion of imports in 2017, according to Global Trade Atlas. The United States is China’s leading supplier of intravenous diagnostic equipment, therapeutic devices, diagnostic equipment, and other relatively higher-value products.

U.S. Reliance on Offshoring

The relatively high volume of U.S. imports of Chinese parts and components largely reflects a supply chain strategy of U.S. firms aimed at lowering their production costs. More specifically, by importing low-value components from countries associated with low-labor costs (Mexico and China), U.S. producers have long been able to specialize in producing finished goods of high value. These transactions occur in one of two ways: (1) firms establish manufacturing facilities in China (i.e., offshoring) and then import parts directly from these affiliates, or (2) U.S.-based firms import these goods from local Chinese companies (i.e., outsourcing).

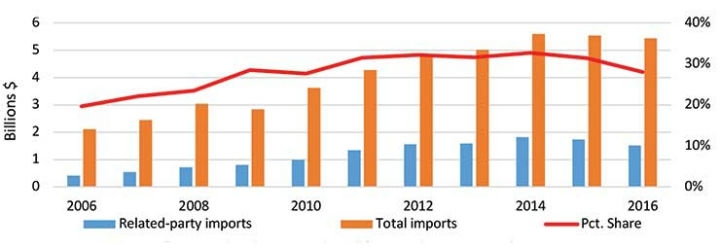

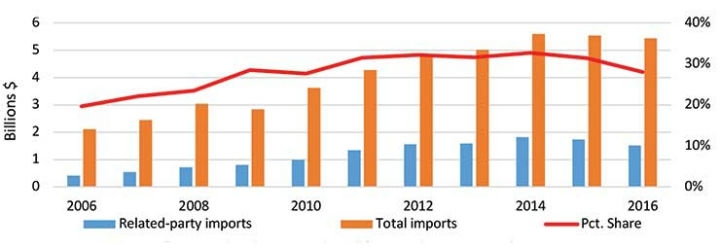

For much of the previous 15 years, U.S. firms have invested more than $800 million—nearly as much as all other countries combined—into China’s medtech sector, according to a recent query of the fDi Intelligence database. Nearly 80 percent ($641 million) of these projects have been aimed at constructing new manufacturing facilities or expanding upon existing factories. These investments have translated into relatively high amounts of imports by U.S. multinationals from their affiliates in China, suggesting the prevalence of offshoring by the U.S. industry. Between one-fifth and one-third of U.S. medtech imports from China since 2006 have been attributable to these transactions, otherwise known as “related-party transfers” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: U.S. medical device imports from China by related-parties, total imports, and percentage share (related-parties/total imports), 2006-16. Source: U.S. Census Bureau “NAICS Related Party Database,” (accessed Aug. 13, 2018).

Improving Chinese Innovation

In addition to attracting substantial amounts of foreign direct investment into the medtech sector, China has also implemented a number of policies aimed at bolstering the innovative capacity of its local companies. These policies are largely seen as a vehicle for facilitating the transition of local producers away from low-cost manufacturing into higher segments of the global value chain. For example, among the priorities listed in China’s 2011–15 five-year plan from the Ministry of Science and Technology is the advancement of local manufacturers in high-end medtech sectors, such as diagnostic imaging. Further, China’s domestic firms have been the leading beneficiaries of a 2014 policy aimed at expediting the regulatory approval for devices deemed “innovative,” such as digital radiography. At the same time, China has implemented policies that have extended the time to market for some foreign devices, which could put these producers at a disadvantage relative to local firms. For example, foreign manufacturers of some Class II and Class III devices have been required to conduct local clinical trials before gaining sales approval in China, which is an important departure from international best practices.

Perhaps the most notable policy is the “Made in China 2025” initiative. This plan, which the Chinese government announced in 2015, identified 10 sectors ranging from renewable energy to mobile phone chips to high performance medical technology, in which the country would like to become a global leader and supply more of its domestic market. According to the Mercator Institute for China Studies, China has established ambitious market share target it intends to supply by indigenous production: 50 percent by 2020 and 70 percent by 2025. By some accounts, China remains far from meeting these goals; multinationals represent the majority of China’s high-end medtech market and more than 80 percent of Chinese firms are small players, according to various industry representatives.

Setting the Stage for 301 Tariffs

With regard to the imposition of 301 tariffs, Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. Trade Representative, has identified the role of “Made in China 2025” as a motivating factor. Specifically, the ambassador released a statement announcing the 301 tariffs, calling attention to “Chinese imports containing industrially significant technologies” that have been prioritized under the “Made in China 2025” program. In addition, the statement revealed its findings from the Section 301 investigation, which underscored China’s attempts to “…undermine America’s high-tech industries and economic leadership through unfair trade practices and industrial policies.”2

As previously stated, more than $2.7 billion (6 percent) of the $50 billion in tariffs against China covers HTS categories for medical devices and related components used in the production of final goods. Examples include circuit boards, disk drives, and motor parts. Further, of the $5.4 billion in U.S. imports of medical devices from China in 2017, almost half (49 percent) will face tariffs.

Putting it All Together

The United States is the world’s most competitive medical device industry,3 with seven of the 10 largest firms (by sales) headquartered domestically. Much of this competitiveness is rooted in the ability of these firms to source relatively inexpensive parts and components from their affiliates in countries like China, for use in final goods production. Although Section 301 tariffs were fashioned, at least in part, to respond to China’s discriminatory industrial policies, initial evidence suggests they may have the unintended consequence of raising production costs on U.S. multinational corporations that import components from their Chinese affiliates. This is largely reflected in the importance of related-party transfers between U.S. firms and their Chinese affiliates. Although alternative suppliers may be available for U.S. medtech manufacturers, switching suppliers is likely to be costly and time consuming, given the demands of gaining certification under international standards for quality assessments across the supply chain.

References

Mihir Torsekar covers trade and competitiveness issues affecting the U.S. and global medical device industry as part of his duties at the United States International Trade Commission.

Section 301 Tariffs Hit Medical Devices

On July 6, 2018, the United States announced tariffs of 25 percent on $34 billion worth of imports from China (818 products), with an additional $16 billion (284 products)1 unveiled on August 23. These measures were made in response to Section 301 investigations, which the United States initiated in August 2017 to determine the possible impact of China’s forced technology transfer and intellectual property practices on U.S. national security interests.

Medical devices and related parts factored prominently into these actions, representing about 6 percent ($2.7 billion) of the value of the tariffs currently being assessed. Further, dutiable medtech goods equated to nearly half of all U.S. medtech imports from China in 2017. China has since responded by applying 25 percent tariffs on medtech imports worth $4.7 billion—roughly 85 percent of its sectoral U.S. imports in 2017.

U.S.-China Trade Overview

The United States is the world’s largest importer of medical technology and relies heavily on imports from China, its fourth largest supplier (after Mexico, Ireland, and Germany). The bilateral trade deficit between the United States and China for medtech has been growing slightly in recent years, reaching $711 million in 2017, driven principally by U.S. imports of Chinese-made parts and components (Figure 1). The goods for which the United States has maintained its highest trade deficits with China consist mostly of parts for devices such as X-ray machines and orthopedic implants as well as disposables like surgical gloves and bandages.

Figure 1: U.S. medical device imports, exports, and total trade with China, 2012–17 (left); 2017 U.S. medical device imports by parts and all other devices (right). Source: IHS Markit, Global Trade Atlas (accessed Feb. 21, 2019).

At the same time, the United States is China’s largest supplier of medical technology, accounting for close to one-third of that country’s $18.6 billion of imports in 2017, according to Global Trade Atlas. The United States is China’s leading supplier of intravenous diagnostic equipment, therapeutic devices, diagnostic equipment, and other relatively higher-value products.

U.S. Reliance on Offshoring

The relatively high volume of U.S. imports of Chinese parts and components largely reflects a supply chain strategy of U.S. firms aimed at lowering their production costs. More specifically, by importing low-value components from countries associated with low-labor costs (Mexico and China), U.S. producers have long been able to specialize in producing finished goods of high value. These transactions occur in one of two ways: (1) firms establish manufacturing facilities in China (i.e., offshoring) and then import parts directly from these affiliates, or (2) U.S.-based firms import these goods from local Chinese companies (i.e., outsourcing).

For much of the previous 15 years, U.S. firms have invested more than $800 million—nearly as much as all other countries combined—into China’s medtech sector, according to a recent query of the fDi Intelligence database. Nearly 80 percent ($641 million) of these projects have been aimed at constructing new manufacturing facilities or expanding upon existing factories. These investments have translated into relatively high amounts of imports by U.S. multinationals from their affiliates in China, suggesting the prevalence of offshoring by the U.S. industry. Between one-fifth and one-third of U.S. medtech imports from China since 2006 have been attributable to these transactions, otherwise known as “related-party transfers” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: U.S. medical device imports from China by related-parties, total imports, and percentage share (related-parties/total imports), 2006-16. Source: U.S. Census Bureau “NAICS Related Party Database,” (accessed Aug. 13, 2018).

Improving Chinese Innovation

In addition to attracting substantial amounts of foreign direct investment into the medtech sector, China has also implemented a number of policies aimed at bolstering the innovative capacity of its local companies. These policies are largely seen as a vehicle for facilitating the transition of local producers away from low-cost manufacturing into higher segments of the global value chain. For example, among the priorities listed in China’s 2011–15 five-year plan from the Ministry of Science and Technology is the advancement of local manufacturers in high-end medtech sectors, such as diagnostic imaging. Further, China’s domestic firms have been the leading beneficiaries of a 2014 policy aimed at expediting the regulatory approval for devices deemed “innovative,” such as digital radiography. At the same time, China has implemented policies that have extended the time to market for some foreign devices, which could put these producers at a disadvantage relative to local firms. For example, foreign manufacturers of some Class II and Class III devices have been required to conduct local clinical trials before gaining sales approval in China, which is an important departure from international best practices.

Perhaps the most notable policy is the “Made in China 2025” initiative. This plan, which the Chinese government announced in 2015, identified 10 sectors ranging from renewable energy to mobile phone chips to high performance medical technology, in which the country would like to become a global leader and supply more of its domestic market. According to the Mercator Institute for China Studies, China has established ambitious market share target it intends to supply by indigenous production: 50 percent by 2020 and 70 percent by 2025. By some accounts, China remains far from meeting these goals; multinationals represent the majority of China’s high-end medtech market and more than 80 percent of Chinese firms are small players, according to various industry representatives.

Setting the Stage for 301 Tariffs

With regard to the imposition of 301 tariffs, Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. Trade Representative, has identified the role of “Made in China 2025” as a motivating factor. Specifically, the ambassador released a statement announcing the 301 tariffs, calling attention to “Chinese imports containing industrially significant technologies” that have been prioritized under the “Made in China 2025” program. In addition, the statement revealed its findings from the Section 301 investigation, which underscored China’s attempts to “…undermine America’s high-tech industries and economic leadership through unfair trade practices and industrial policies.”2

As previously stated, more than $2.7 billion (6 percent) of the $50 billion in tariffs against China covers HTS categories for medical devices and related components used in the production of final goods. Examples include circuit boards, disk drives, and motor parts. Further, of the $5.4 billion in U.S. imports of medical devices from China in 2017, almost half (49 percent) will face tariffs.

Putting it All Together

The United States is the world’s most competitive medical device industry,3 with seven of the 10 largest firms (by sales) headquartered domestically. Much of this competitiveness is rooted in the ability of these firms to source relatively inexpensive parts and components from their affiliates in countries like China, for use in final goods production. Although Section 301 tariffs were fashioned, at least in part, to respond to China’s discriminatory industrial policies, initial evidence suggests they may have the unintended consequence of raising production costs on U.S. multinational corporations that import components from their Chinese affiliates. This is largely reflected in the importance of related-party transfers between U.S. firms and their Chinese affiliates. Although alternative suppliers may be available for U.S. medtech manufacturers, switching suppliers is likely to be costly and time consuming, given the demands of gaining certification under international standards for quality assessments across the supply chain.

References

- This product list is slightly lower than the 1,333 product categories that were initially proposed in April 2018.

- “USTR issues Tariffs on Chinese Products in Response to Unfair Trade Practices,” June 15, 2018. https://bit.ly/2MtOfQ2

- Herman, Horowitz, and Torsekar, “Competitive Conditions Affecting U.S. Exports of Medical Technology,” August 2018.

Mihir Torsekar covers trade and competitiveness issues affecting the U.S. and global medical device industry as part of his duties at the United States International Trade Commission.