Mihir Torsekar, International Trade Analyst, U.S. International Trade Commission10.08.19

China has quickly emerged as the epicenter of the global medtech supply chain. The country’s unique blend of low labor costs, burgeoning market, and domestic policies aimed at attracting foreign capital have all played a role. However, the ongoing trade dispute with the United States has raised fresh concerns about the viability of investing in China. This concern, coupled with China’s diminishing reputation as a low-cost manufacturer, has led manufacturers to diversify their investments to other regional players in recent years. This article explores the implications for three emerging suppliers in the region: Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam.

China’s Changing Conditions

China has long attracted investment from U.S. medtech firms seeking to lower their production costs and to supply the local market. Capitalizing on the country’s low labor costs, these firms often offshored production to a local affiliate or outsourced these activities to a contractor or Chinese companies. The resulting parts and components were then imported back to the United States for final production. However, two relatively recent developments may be causing a rethink of this strategy.

The first, and most recent, is the year-long trade dispute between the United States and China. Beginning in July 2018, the United States implemented the first round of its Section 301 tariffs on the country. At the time of writing, these tariffs covered about $200 billion worth of imports from China, with another $300 billion expected by Sept. 1. Medical products have been implicated in these actions to the tune of nearly $1 billion, or close to one-fifth the value of all U.S. medtech imports from China. Given that roughly one-third of U.S. medtech imports from China represent transactions between parent companies and their Chinese affiliates, these tariffs have effectively imposed a tax on many U.S. firms.

The second, and more enduring trend, is China’s rising labor costs. Massive urbanization coupled with the country’s ascension into higher value-added elements of the global supply chain have translated into increased labor costs over the past decade.1 According to IDC Worldwide Robotics, average yearly manufacturing wages in China have risen by 80 percent since 2010. Oxford Economics estimates that labor costs in China are only 4 percent less than those in the United States (when productivity is included).

Asia’s Burgeoning Medtech Cluster

In response to these concerns, medtech multinational corporations (MNCs) have increasingly sought to manage supply chain risks by investing in Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam respectively. During 2008–18, these countries amassed nearly $1 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) to the medtech sector. Notably, Vietnam accounted for just $20 million of this total, but the country is quickly gaining ground. For example, total investment in Vietnam during the first five months of 2019 reached a four-year high of nearly $17 billion and was led by the manufacturing sector.

Owing to these investments, the medtech industries within the three countries features the strong presence of MNCs working alongside local players. For example, Malaysia’s medtech industry includes more than 200 local manufacturers and over 30 MNCs including Agilent, B. Braun, and St. Jude Medical. Local producers in Malaysia and Vietnam are led by small to medium-sized enterprises that produce low-value goods such as hospital gloves. In contrast, MNCs principally produce and supply high-end products to these markets.

Singapore’s medtech industry is composed of more than 60 MNCs and over 220 local, smaller players. In particular, MNCs—including Medtronic, Becton Dickinson, and Thermo Fisher Scientific—have invested in a broad range of capacities from establishing regional headquarters, to manufacturing, to research and development (R&D) activities. As a result, Singapore hosts 50 regional headquarters for the world’s leading medtech firms and maintains 25 medtech R&D centers within its borders. In contrast to Malaysia’s and Vietnam’s predominantly low-tech production, Singapore’s medtech manufacturing is led by medium- to high-tech therapeutic devices like pacemakers and orthopedic implants.

What Is Driving These Investments?

These trends reflect several factors, including competitive production costs (particularly in Malaysia and Vietnam); favorable government policies that encourage foreign investment; and an English-speaking workforce.

With regard to production costs, the World Bank estimates that Malaysia’s wage rates may be lower than China’s, while Vietnam has the lowest in the entire region. Notably, Singapore’s labor costs are among the region’s highest. However, the country’s combination of low energy costs and access to water (which is vital to the production of key inputs for medical devices like semiconductors) have at least partially offset this drawback.2

Another driver is favorable government policies. For example, Malaysia and Singapore both maintain tax-free special economic zones (SEZs) to encourage foreign investment. Moreover, the World Bank recently reported that Vietnam ranked higher (69th place) than China (78th place) in its most recent “Ease of Doing Business Report.”

In addition, all three countries have made significant strides to harmonize their medtech regulatory regimes to international best practices. Regulatory coherence is crucial for accessing foreign markets, but also for ensuring a seamless relationship between OEMs and local partners. In 2012, Malaysia passed the Medical Device Act and the Medical Devices Regulations. These policies codify the country’s risk-based approach to device classification and articulates the registration requirements. Likewise, last summer, Singapore introduced policies aimed at achieving faster market access for lower-risk devices and for mobile health applications, and clarified regulatory requirements for digital and high-risk devices, according to the Emergo Group.

Greater regulatory convergence in the sector can be expected, as each of the three countries is a signatory to the Comprehensive Pacific Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The trade agreement, which includes 11 total countries, phases out tariffs on medical devices traded among the participating economies. Further, the agreement includes an annex on medical devices that addresses issues such as technical barriers to trade and other regulatory-related concerns.

A final competitive advantage is the prevalence of English speakers within these three countries. Given the relatively fragmented nature of medical device supply chains and the potential harm wrought by defective devices, it is critical for OEMs to have open communication with their foreign counterparts. The private sectors in Singapore and Malaysia largely conduct business in English. Moreover, Singapore has been listed as one of Asia’s most prominent English speaking countries, while more than half of Vietnam’s population speaks the language.

Trade Overview and Outlook

Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam have quickly emerged as Asia’s leading and fastest-growing medtech suppliers for the United States. Malaysia’s and Vietnam’s exports to the United States are primarily rubber gloves and other commodities of low value. In contrast, Singapore’s exports have principally comprised therapeutic devices such as implantable joints and other goods of medium-high technology.

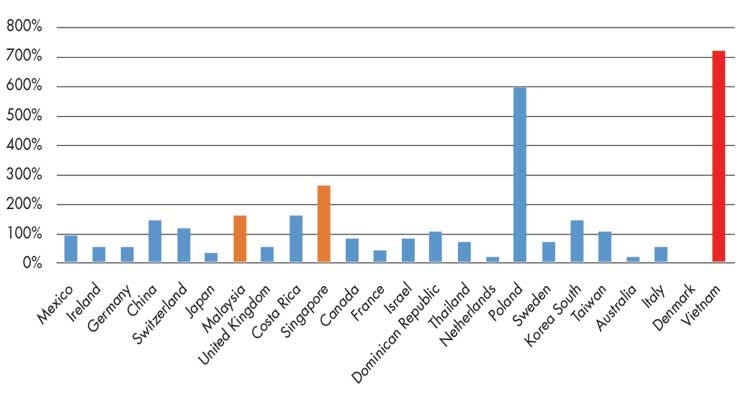

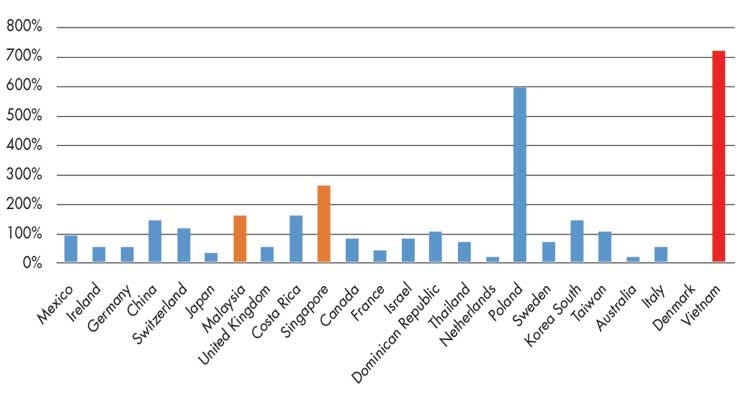

Malaysia and Singapore are both top 10 medtech suppliers to the United States (and top five regional suppliers behind China and Japan). Although Vietnam is only the United States’ 30th largest provider of medtech, the growth rate of U.S. imports from that country has outpaced the rates of any other leading suppliers over the past decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Growth rate of U.S. medtech imports from its top 30 suppliers, 2008-18. Source: IHS Markit, Global Trade Atlas (date accessed Aug. 13, 2019).

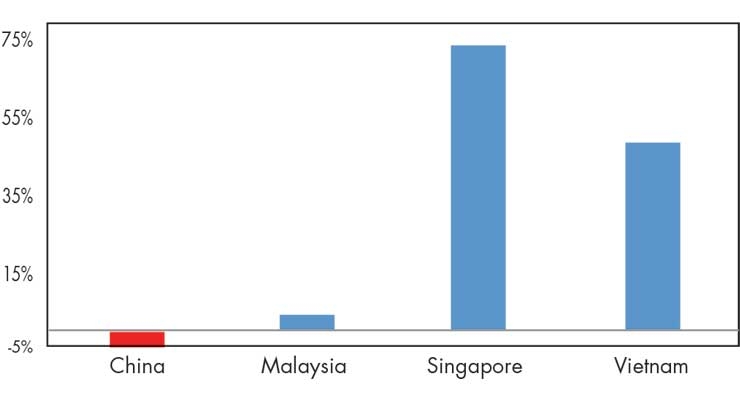

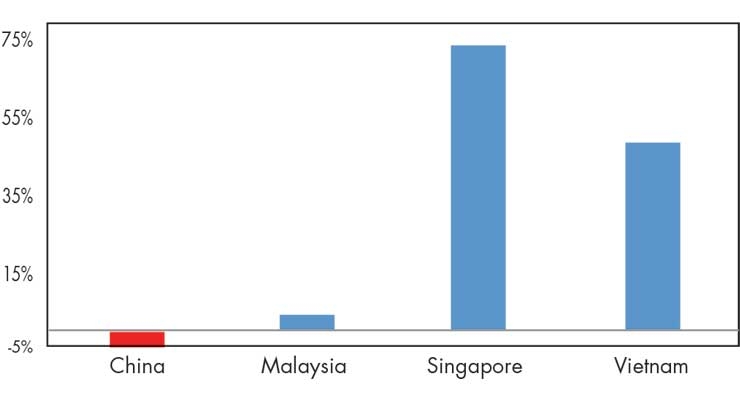

The most recent trade data suggests a possible shift in U.S. imports away from China and towards other regional players (Figure 2). Specifically, during July 2018 (when the first tariffs took effect) to May 2019, U.S. imports from China fell by 6 percent, while Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam each increased their medtech exports to the United States during this time.

Figure 2: Changes in U.S. Medtech Imports from Selected Asian Countries, July 2018–May 2019. Source: Official Statistics from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Aug. 12, 2019.

Final Verdict: China Still Reigns…For Now

Despite rising production costs, owing to tariffs and climbing wages, the appeal of investing in China remains strong. The country’s robust healthcare market, coupled with its entrenched industrial base still make it an attractive opportunity. On the other hand, the outcome of the U.S.–China dispute remains uncertain and may alter the long-term calculus. If so, don’t be surprised to see Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam enlarging their presence in the global medtech supply chain.

References

Mihir Torsekar covers trade and competitiveness issues affecting the U.S. and global medical device industry as part of his duties at the United States International Trade Commission.

China’s Changing Conditions

China has long attracted investment from U.S. medtech firms seeking to lower their production costs and to supply the local market. Capitalizing on the country’s low labor costs, these firms often offshored production to a local affiliate or outsourced these activities to a contractor or Chinese companies. The resulting parts and components were then imported back to the United States for final production. However, two relatively recent developments may be causing a rethink of this strategy.

The first, and most recent, is the year-long trade dispute between the United States and China. Beginning in July 2018, the United States implemented the first round of its Section 301 tariffs on the country. At the time of writing, these tariffs covered about $200 billion worth of imports from China, with another $300 billion expected by Sept. 1. Medical products have been implicated in these actions to the tune of nearly $1 billion, or close to one-fifth the value of all U.S. medtech imports from China. Given that roughly one-third of U.S. medtech imports from China represent transactions between parent companies and their Chinese affiliates, these tariffs have effectively imposed a tax on many U.S. firms.

The second, and more enduring trend, is China’s rising labor costs. Massive urbanization coupled with the country’s ascension into higher value-added elements of the global supply chain have translated into increased labor costs over the past decade.1 According to IDC Worldwide Robotics, average yearly manufacturing wages in China have risen by 80 percent since 2010. Oxford Economics estimates that labor costs in China are only 4 percent less than those in the United States (when productivity is included).

Asia’s Burgeoning Medtech Cluster

In response to these concerns, medtech multinational corporations (MNCs) have increasingly sought to manage supply chain risks by investing in Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam respectively. During 2008–18, these countries amassed nearly $1 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) to the medtech sector. Notably, Vietnam accounted for just $20 million of this total, but the country is quickly gaining ground. For example, total investment in Vietnam during the first five months of 2019 reached a four-year high of nearly $17 billion and was led by the manufacturing sector.

Owing to these investments, the medtech industries within the three countries features the strong presence of MNCs working alongside local players. For example, Malaysia’s medtech industry includes more than 200 local manufacturers and over 30 MNCs including Agilent, B. Braun, and St. Jude Medical. Local producers in Malaysia and Vietnam are led by small to medium-sized enterprises that produce low-value goods such as hospital gloves. In contrast, MNCs principally produce and supply high-end products to these markets.

Singapore’s medtech industry is composed of more than 60 MNCs and over 220 local, smaller players. In particular, MNCs—including Medtronic, Becton Dickinson, and Thermo Fisher Scientific—have invested in a broad range of capacities from establishing regional headquarters, to manufacturing, to research and development (R&D) activities. As a result, Singapore hosts 50 regional headquarters for the world’s leading medtech firms and maintains 25 medtech R&D centers within its borders. In contrast to Malaysia’s and Vietnam’s predominantly low-tech production, Singapore’s medtech manufacturing is led by medium- to high-tech therapeutic devices like pacemakers and orthopedic implants.

What Is Driving These Investments?

These trends reflect several factors, including competitive production costs (particularly in Malaysia and Vietnam); favorable government policies that encourage foreign investment; and an English-speaking workforce.

With regard to production costs, the World Bank estimates that Malaysia’s wage rates may be lower than China’s, while Vietnam has the lowest in the entire region. Notably, Singapore’s labor costs are among the region’s highest. However, the country’s combination of low energy costs and access to water (which is vital to the production of key inputs for medical devices like semiconductors) have at least partially offset this drawback.2

Another driver is favorable government policies. For example, Malaysia and Singapore both maintain tax-free special economic zones (SEZs) to encourage foreign investment. Moreover, the World Bank recently reported that Vietnam ranked higher (69th place) than China (78th place) in its most recent “Ease of Doing Business Report.”

In addition, all three countries have made significant strides to harmonize their medtech regulatory regimes to international best practices. Regulatory coherence is crucial for accessing foreign markets, but also for ensuring a seamless relationship between OEMs and local partners. In 2012, Malaysia passed the Medical Device Act and the Medical Devices Regulations. These policies codify the country’s risk-based approach to device classification and articulates the registration requirements. Likewise, last summer, Singapore introduced policies aimed at achieving faster market access for lower-risk devices and for mobile health applications, and clarified regulatory requirements for digital and high-risk devices, according to the Emergo Group.

Greater regulatory convergence in the sector can be expected, as each of the three countries is a signatory to the Comprehensive Pacific Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The trade agreement, which includes 11 total countries, phases out tariffs on medical devices traded among the participating economies. Further, the agreement includes an annex on medical devices that addresses issues such as technical barriers to trade and other regulatory-related concerns.

A final competitive advantage is the prevalence of English speakers within these three countries. Given the relatively fragmented nature of medical device supply chains and the potential harm wrought by defective devices, it is critical for OEMs to have open communication with their foreign counterparts. The private sectors in Singapore and Malaysia largely conduct business in English. Moreover, Singapore has been listed as one of Asia’s most prominent English speaking countries, while more than half of Vietnam’s population speaks the language.

Trade Overview and Outlook

Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam have quickly emerged as Asia’s leading and fastest-growing medtech suppliers for the United States. Malaysia’s and Vietnam’s exports to the United States are primarily rubber gloves and other commodities of low value. In contrast, Singapore’s exports have principally comprised therapeutic devices such as implantable joints and other goods of medium-high technology.

Malaysia and Singapore are both top 10 medtech suppliers to the United States (and top five regional suppliers behind China and Japan). Although Vietnam is only the United States’ 30th largest provider of medtech, the growth rate of U.S. imports from that country has outpaced the rates of any other leading suppliers over the past decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Growth rate of U.S. medtech imports from its top 30 suppliers, 2008-18. Source: IHS Markit, Global Trade Atlas (date accessed Aug. 13, 2019).

The most recent trade data suggests a possible shift in U.S. imports away from China and towards other regional players (Figure 2). Specifically, during July 2018 (when the first tariffs took effect) to May 2019, U.S. imports from China fell by 6 percent, while Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam each increased their medtech exports to the United States during this time.

Figure 2: Changes in U.S. Medtech Imports from Selected Asian Countries, July 2018–May 2019. Source: Official Statistics from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Aug. 12, 2019.

Final Verdict: China Still Reigns…For Now

Despite rising production costs, owing to tariffs and climbing wages, the appeal of investing in China remains strong. The country’s robust healthcare market, coupled with its entrenched industrial base still make it an attractive opportunity. On the other hand, the outcome of the U.S.–China dispute remains uncertain and may alter the long-term calculus. If so, don’t be surprised to see Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam enlarging their presence in the global medtech supply chain.

References

- Torsekar, “China Climbs the Global Value Chain for Medical Devices,” March 2018.

- Torsekar and VerWey, “East Asia-Pacific’s Participation in the Global Value Chain for Electronic Products,” March 2019.

Mihir Torsekar covers trade and competitiveness issues affecting the U.S. and global medical device industry as part of his duties at the United States International Trade Commission.