Ranica Arrowsmith, Associate Editor09.12.13

Medical Product Outsourcing ran a feature on process validation in medical device manufacturing in its September issue. Here are some further insights from Tom Flannery, chief operating officer of Iapyx Medical, a San Diego, Calif.-based maker of infection prevention technology.

Iapyx, which gets its name from the Greek god of healing, is a small medical device company that focuses on infection prevention from respiratory care devices in and around the hospital. According to Flannery, Iapyx deliberately does not have a large Internet presence because it prefers to fashion itself as a “virtual company.” The company has three primary partners: the inventor, the director of operations (Flannery) who manages supply chain and supply side, and the CEO, who negotiates private labeling deals.

Flannery joined Iapyx from Nypro (now owned by Jabil), a precision injection molding and contract manufacturing company, where he was general manager of their Tijuana, Mexico, manufacturing facility for twelve years. It was there that he gained an intimate knowledge with process validation procedures.

“A lot of people look at validation as a check-the-box type of activity, and then they move forward,” Flannery told MPO. “And I’m not just talking about small companies—I’m talking about large, global medical device entities. Really, validation paints a picture that must be maintained through the life of the device, and it can be adjusted. But the important thing to look at in validation is you do not want to look at it as the check-the-box activity that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says you should. Most companies lose the validated stage shortly after they’ve completed the validation because there’s no statistical tie-in to what they do after production. So they do all these tests, they’ll launch into production, and then their release criteria aren’t comprehensive to the validation. Therefore, they’re not able to prove to themselves or to their end-user that what they’re doing in production is maintaining that validated state. Every one of those critical quality criteria that you establish in validation needs to be verified going forward.”

The FDA puts forth the following definition and criteria for retrospective validation:

“Retrospective validation is the validation of a process based on accumulated historical production, testing, control, and other information for a product already in production and distribution. This type of validation makes use of historical data and information which may be found in batch records, production log books, lot records, control charts, test and inspection results, customer complaints or lack of complaints, field failure reports, service reports, and audit reports. Historical data must contain enough information to provide an in-depth picture of how the process has been operating and whether the product has consistently met its specifications. Retrospective validation may not be feasible if all the appropriate data was not collected, or appropriate data was not collected in a manner which allows adequate analysis.”

“Retrospective validations are used when you’ve determined something is critical to quality that was not originally anticipated in the validation,” said Flannery. “You would then look backward and ask, based on what we know today, what are the operating ranges by which we can manufacture the product that we know its going to be good statistically speaking? Not qualitatively speaking, but quantitatively speaking. That’s the beauty of the end-user market: Ultimately, you’ll find out that people are going to use your devices in ways that you never intended them to be used.

“One example: We had an angiography device. During the validation, it was subjected to 1,000 pounds of pressure. The device was comprised of a syringe, a manifold and a hand controller pit that saw extreme amounts of pressure under operation, not on the patient side, but on the side of injecting the contrast through the device. What we learned was that initially, when the product was launched in the market, the introducer catheter, when used in the femoral artery, was rather large. Large holes in the femoral artery bleed, and they take a long time to heal. So, that entire market had gone smaller. We had been in the market for years with this device with no issues, and all of a sudden we started getting these complaints from very specific hospitals. They had started using smaller catheters, which raised the pressure enough to cause the product to fail. So we had to go back and re-design. In validation, you give yourself the widest possible window for success, because you don’t want to be verifying your process more than necessary—in other words, more than what is required by user needs. The re-design of our product cost hundred of thousands—if not millions—of dollars, and that was all because of the way in which the market used the device. Probably the most common need to go back and revalidate something looking backward is when the market uses your product in a way that the engineers didn’t anticipate.”

The importance of collaboration in process validation

Flannery says the idea of collaboration is “really missed” in the whole process of validation.

“You get 10 engineers in a room talking about what’s important about the device, and they‘re going to talk about what’s important about that device from an engineering perspective,” he explained. “Very seldom do you see a clinician or someone who really understands the patient participate in that process. I cannot tell you how many times we’ve invested countless engineering hours reducing variation—because that’s what’s it’s all about, variation is the enemy, that’s what causes defects. But defects are defined by the user—and that’s my point. We’ll spend thousands of dollars and hours developing a process to eliminate variation that’s not important to the end user. On the other side of that coin is something very simple that is a problem to the end-user, and you get your product out there on market, and then you’ll be doing retrospective validations to figure out what your capabilities are around a particular process so you can go back and improve it.

“The world-class companies really understand that validation is not just check-the-box. You’re creating a state, and if you can prove that you’re maintaining that state, design controls and all of the things that flow out of design controls such as change control and process development become crystal clear. And I would say—and I’ve only seldom seen this happen because it’s expensive—in many cases before you even make part number one, you should be able to tell even in a manual process that you’re maintaining a validated state through a few simple sates like a line clearance (where quality will release a process after verifying the machine settings, the material revision levels, operator training, etc.).”

What does an OEM like Iapyx expect from contract manufacturing organization (CMO) partners?

“I need a little more support on the engineering side because we don’t have a staff of engineers at Iapyx, but aside from that, in general, what Iapyx looks for is relatively unique because of our size and the fact that we try to stay ‘virtual,’ keeping our overhead low,” Flannery said. “I look for a full-service manufacturer who is on the same page as me philosophically—first, because trying to change someone’s mindset takes years, and once they’ve realized that there’s value in it, its too late. You have to make sure that your CMO is on the same page as you are. I have a company I’ve worked with for a year that is on the same page as me philosophically, but their challenge is implementing the systems necessary to be effective. That’s really the next thing. Once you recognize that your CMO philosophically understands what it is you’re talking about when you say ‘process validation’—that it’s not just an activity that they have to complete in order to be in compliance—then it’s whether they have the tools to accomplish the mission. This isn’t a difficult task.

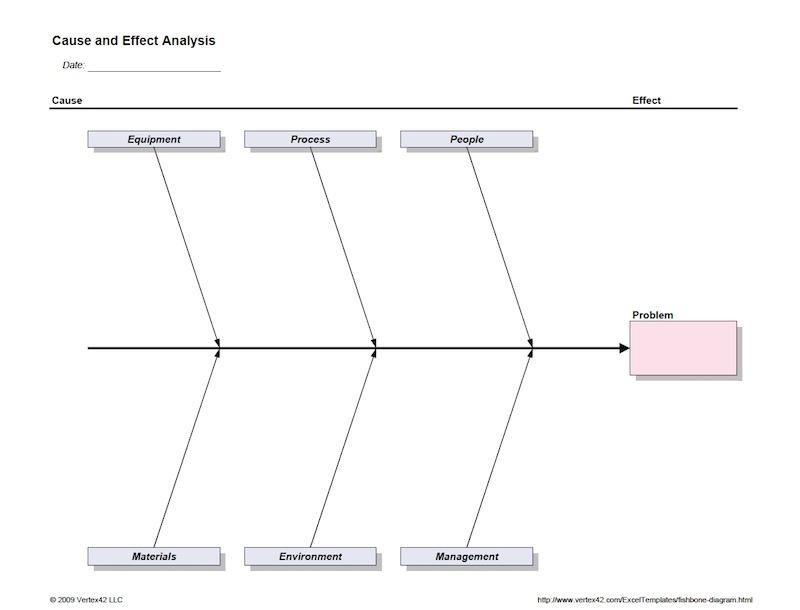

“When I was at Nypro, we developed a relatively standard system that accomplished 80 percent of the objectives and the other 20 percent was left up to the engineers to develop. We had standard procedures and a firm understanding of the need to be able to prove with each lot released that the validated state was maintained. Our system was really good at change control. If changes are made and the device master record1 is not maintained—and I’m not just talking about the component dimensional level, I’m talking about work constructions, environmental controls, change controls to the entire fishbone (Figure 1) of all the inputs all the way down to when you do preventative maintenance on a piece of equipment. The preventative maintenance should go into the device history record for the lots that were being produced before and after that repair occurred, so that in the event of a subsequent defect, the whole picture of the lot is present.

Fig. 1: The cause and effect diagram, or fishbone diagram, is commonly used in process validation to keep track of every input to a device. It provides a simply way to determine where a problem, if one emerges, could have originated.

“So I would say the top three [areas we look for in CMOs] beyond philosophy is effective change control; effective engineering tools for implementing and maintaining validated state, and really solid communication. The OEM needs to participate in this process. You cannot expect a CMO to understand the patient needs. And that’s really where the OEM really falls short—understanding what is going to impact the patient. Most of the time, the OEM has the same kind of manufacturing engineers working with the CMO—that’s exactly the wrong thing, because if you pick the right CMO, they should have the capabilities to do that. They need to have the marketing personnel working with the people who are touching the patient, who understand how the device is used and what it needs to do and what’s going to improve patient care.

“When we did our validation on our closed section catheter, we were fortunate enough to work with a doctor who has more than 30 years having used a similar device. He worked with us on the little idiosyncrasies of the device and what the clinician/respiratory therapist would benefit from being able to use. I felt it was probably the most comprehensive validation from the patient perspective that I’ve ever conducted in my entire career, and I’ve conducted validations on hydro surgery devices and angiogram devices where we’re talking real patient safety concerns. This was an airway suction catheter, which granted has similar patient concerns, but it’s a device that has 40-plus years of effective use on the market. The patient has got to come first in this process, and most of the time it’s too much about process and not enough about patient.”

1. The device master record is a comprehensive collection of every single process and input that has affected a device during manufacture.

For the full feature on process validation, see the September issue of MPO.

Iapyx, which gets its name from the Greek god of healing, is a small medical device company that focuses on infection prevention from respiratory care devices in and around the hospital. According to Flannery, Iapyx deliberately does not have a large Internet presence because it prefers to fashion itself as a “virtual company.” The company has three primary partners: the inventor, the director of operations (Flannery) who manages supply chain and supply side, and the CEO, who negotiates private labeling deals.

Flannery joined Iapyx from Nypro (now owned by Jabil), a precision injection molding and contract manufacturing company, where he was general manager of their Tijuana, Mexico, manufacturing facility for twelve years. It was there that he gained an intimate knowledge with process validation procedures.

“A lot of people look at validation as a check-the-box type of activity, and then they move forward,” Flannery told MPO. “And I’m not just talking about small companies—I’m talking about large, global medical device entities. Really, validation paints a picture that must be maintained through the life of the device, and it can be adjusted. But the important thing to look at in validation is you do not want to look at it as the check-the-box activity that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says you should. Most companies lose the validated stage shortly after they’ve completed the validation because there’s no statistical tie-in to what they do after production. So they do all these tests, they’ll launch into production, and then their release criteria aren’t comprehensive to the validation. Therefore, they’re not able to prove to themselves or to their end-user that what they’re doing in production is maintaining that validated state. Every one of those critical quality criteria that you establish in validation needs to be verified going forward.”

The FDA puts forth the following definition and criteria for retrospective validation:

“Retrospective validation is the validation of a process based on accumulated historical production, testing, control, and other information for a product already in production and distribution. This type of validation makes use of historical data and information which may be found in batch records, production log books, lot records, control charts, test and inspection results, customer complaints or lack of complaints, field failure reports, service reports, and audit reports. Historical data must contain enough information to provide an in-depth picture of how the process has been operating and whether the product has consistently met its specifications. Retrospective validation may not be feasible if all the appropriate data was not collected, or appropriate data was not collected in a manner which allows adequate analysis.”

“Retrospective validations are used when you’ve determined something is critical to quality that was not originally anticipated in the validation,” said Flannery. “You would then look backward and ask, based on what we know today, what are the operating ranges by which we can manufacture the product that we know its going to be good statistically speaking? Not qualitatively speaking, but quantitatively speaking. That’s the beauty of the end-user market: Ultimately, you’ll find out that people are going to use your devices in ways that you never intended them to be used.

“One example: We had an angiography device. During the validation, it was subjected to 1,000 pounds of pressure. The device was comprised of a syringe, a manifold and a hand controller pit that saw extreme amounts of pressure under operation, not on the patient side, but on the side of injecting the contrast through the device. What we learned was that initially, when the product was launched in the market, the introducer catheter, when used in the femoral artery, was rather large. Large holes in the femoral artery bleed, and they take a long time to heal. So, that entire market had gone smaller. We had been in the market for years with this device with no issues, and all of a sudden we started getting these complaints from very specific hospitals. They had started using smaller catheters, which raised the pressure enough to cause the product to fail. So we had to go back and re-design. In validation, you give yourself the widest possible window for success, because you don’t want to be verifying your process more than necessary—in other words, more than what is required by user needs. The re-design of our product cost hundred of thousands—if not millions—of dollars, and that was all because of the way in which the market used the device. Probably the most common need to go back and revalidate something looking backward is when the market uses your product in a way that the engineers didn’t anticipate.”

The importance of collaboration in process validation

Flannery says the idea of collaboration is “really missed” in the whole process of validation.

“You get 10 engineers in a room talking about what’s important about the device, and they‘re going to talk about what’s important about that device from an engineering perspective,” he explained. “Very seldom do you see a clinician or someone who really understands the patient participate in that process. I cannot tell you how many times we’ve invested countless engineering hours reducing variation—because that’s what’s it’s all about, variation is the enemy, that’s what causes defects. But defects are defined by the user—and that’s my point. We’ll spend thousands of dollars and hours developing a process to eliminate variation that’s not important to the end user. On the other side of that coin is something very simple that is a problem to the end-user, and you get your product out there on market, and then you’ll be doing retrospective validations to figure out what your capabilities are around a particular process so you can go back and improve it.

“The world-class companies really understand that validation is not just check-the-box. You’re creating a state, and if you can prove that you’re maintaining that state, design controls and all of the things that flow out of design controls such as change control and process development become crystal clear. And I would say—and I’ve only seldom seen this happen because it’s expensive—in many cases before you even make part number one, you should be able to tell even in a manual process that you’re maintaining a validated state through a few simple sates like a line clearance (where quality will release a process after verifying the machine settings, the material revision levels, operator training, etc.).”

What does an OEM like Iapyx expect from contract manufacturing organization (CMO) partners?

“I need a little more support on the engineering side because we don’t have a staff of engineers at Iapyx, but aside from that, in general, what Iapyx looks for is relatively unique because of our size and the fact that we try to stay ‘virtual,’ keeping our overhead low,” Flannery said. “I look for a full-service manufacturer who is on the same page as me philosophically—first, because trying to change someone’s mindset takes years, and once they’ve realized that there’s value in it, its too late. You have to make sure that your CMO is on the same page as you are. I have a company I’ve worked with for a year that is on the same page as me philosophically, but their challenge is implementing the systems necessary to be effective. That’s really the next thing. Once you recognize that your CMO philosophically understands what it is you’re talking about when you say ‘process validation’—that it’s not just an activity that they have to complete in order to be in compliance—then it’s whether they have the tools to accomplish the mission. This isn’t a difficult task.

“When I was at Nypro, we developed a relatively standard system that accomplished 80 percent of the objectives and the other 20 percent was left up to the engineers to develop. We had standard procedures and a firm understanding of the need to be able to prove with each lot released that the validated state was maintained. Our system was really good at change control. If changes are made and the device master record1 is not maintained—and I’m not just talking about the component dimensional level, I’m talking about work constructions, environmental controls, change controls to the entire fishbone (Figure 1) of all the inputs all the way down to when you do preventative maintenance on a piece of equipment. The preventative maintenance should go into the device history record for the lots that were being produced before and after that repair occurred, so that in the event of a subsequent defect, the whole picture of the lot is present.

Fig. 1: The cause and effect diagram, or fishbone diagram, is commonly used in process validation to keep track of every input to a device. It provides a simply way to determine where a problem, if one emerges, could have originated.

“So I would say the top three [areas we look for in CMOs] beyond philosophy is effective change control; effective engineering tools for implementing and maintaining validated state, and really solid communication. The OEM needs to participate in this process. You cannot expect a CMO to understand the patient needs. And that’s really where the OEM really falls short—understanding what is going to impact the patient. Most of the time, the OEM has the same kind of manufacturing engineers working with the CMO—that’s exactly the wrong thing, because if you pick the right CMO, they should have the capabilities to do that. They need to have the marketing personnel working with the people who are touching the patient, who understand how the device is used and what it needs to do and what’s going to improve patient care.

“When we did our validation on our closed section catheter, we were fortunate enough to work with a doctor who has more than 30 years having used a similar device. He worked with us on the little idiosyncrasies of the device and what the clinician/respiratory therapist would benefit from being able to use. I felt it was probably the most comprehensive validation from the patient perspective that I’ve ever conducted in my entire career, and I’ve conducted validations on hydro surgery devices and angiogram devices where we’re talking real patient safety concerns. This was an airway suction catheter, which granted has similar patient concerns, but it’s a device that has 40-plus years of effective use on the market. The patient has got to come first in this process, and most of the time it’s too much about process and not enough about patient.”

1. The device master record is a comprehensive collection of every single process and input that has affected a device during manufacture.

For the full feature on process validation, see the September issue of MPO.