Michael Barbella, Managing Editor02.03.21

Scott Frey grew up watching multiple sclerosis slowly ravage his mother’s body.

Frey recalls the muscle weakness, the spasticity, and lack of balance that stripped his beloved parent of her independence, but mostly he remembers the loss of hand function that rendered even the simplest tasks next to impossible.

“...one of the things she struggled most with as that disease progressed was the use of her hands,” Frey, Miller Family Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Missouri, recounted in an early January podcast. “I remember as a child being very aware of just how important it is to have good hand function in order to live independently and to do all those things that when we’re healthy, we really take for granted—dressing, caring for the house, and taking care of business; most of those activities to some degree involve our hands. I was, in essence, my mom’s hands from the time I was really little and I think that planted the seed in me...”

That seed eventually fostered Frey’s interest in brain-hand communication and the complex neural networks involved in basic motor function. His career in neuroscience has yielded quite a bounty of accomplishments—more than 100 scholarly articles on brain-hand behaviors, and groundbreaking research about neuro-rehabilitation (in 2019, he and a study team at MU found proof that human brains can rewire themselves after a trauma like amputation).

Frey’s latest undertaking could prove equally as trailblazing: He currently is harvesting real-time data on hand function to help craft personalized treatments for severe upper limb injuries. The information collection system he devised uses small wireless sensors embedded within a wearable device (similar to a commercial fitness tracker) to monitor limb function among non-amputees.

Leveraging a $1.5 million federal grant, Frey will use the sensor-generated data to compare standard lab-based assessments for hand behavior/function with real life, daily limb use.

“We can record data with these wireless sensors across numerous days and boil that down to a unique personalized profile of how a person is using their limbs or their prosthesis in the real world,” Frey said, “and then ideally we’ll be able to work with clinicians to develop more effective interventions and evaluate the effectiveness of those interventions in these individuals.”

“This is kind of a new adventure for me,” Frey continued. “This is an area that has grown out of my interest in connecting brain science with real-world behavior.”

The conduit for that connection, of course, is the wireless sensor, an Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) byproduct and hallmark of digital medicine. Sensors are just one of the many upshots of an IoMT-induced connected ecosystem that increasingly is being driven by healthcare data management, value-based care reimbursement models, and personalized medicine.

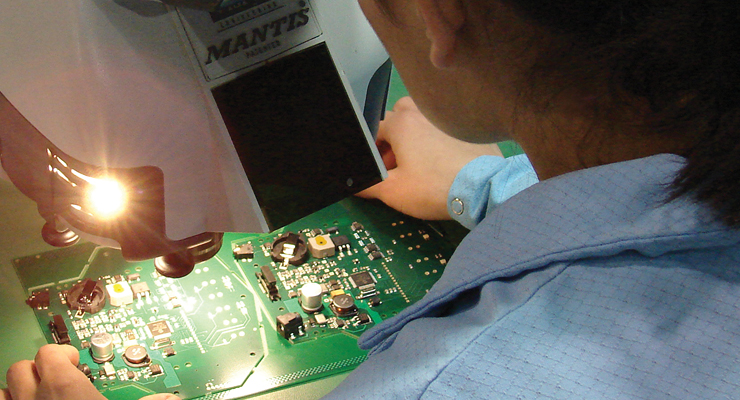

IoMT devices use embedded electronics and sensors to collect, record, and communicate real-time patient data. These electronic components have become smaller, more customized, and in some cases, more powerful to better facilitate interventions and reduce unnecessary clinical visits. The latter objective—now critical in light of the coronavirus pandemic—has spawned skyrocketing demand in the past year for telehealth services and remote patient monitoring technology.

Such demand consequently bolstered the role of electronics manufacturing services (EMS) providers as they worked to maintain device connectivity and helped customers navigate supply chain snafus and essential equipment shortages in COVID-19’s infancy.

This article is featured in the MPO eBook "Engaging Electronics." Click here to download the eBook and finish reading this article.

Frey recalls the muscle weakness, the spasticity, and lack of balance that stripped his beloved parent of her independence, but mostly he remembers the loss of hand function that rendered even the simplest tasks next to impossible.

“...one of the things she struggled most with as that disease progressed was the use of her hands,” Frey, Miller Family Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Missouri, recounted in an early January podcast. “I remember as a child being very aware of just how important it is to have good hand function in order to live independently and to do all those things that when we’re healthy, we really take for granted—dressing, caring for the house, and taking care of business; most of those activities to some degree involve our hands. I was, in essence, my mom’s hands from the time I was really little and I think that planted the seed in me...”

That seed eventually fostered Frey’s interest in brain-hand communication and the complex neural networks involved in basic motor function. His career in neuroscience has yielded quite a bounty of accomplishments—more than 100 scholarly articles on brain-hand behaviors, and groundbreaking research about neuro-rehabilitation (in 2019, he and a study team at MU found proof that human brains can rewire themselves after a trauma like amputation).

Frey’s latest undertaking could prove equally as trailblazing: He currently is harvesting real-time data on hand function to help craft personalized treatments for severe upper limb injuries. The information collection system he devised uses small wireless sensors embedded within a wearable device (similar to a commercial fitness tracker) to monitor limb function among non-amputees.

Leveraging a $1.5 million federal grant, Frey will use the sensor-generated data to compare standard lab-based assessments for hand behavior/function with real life, daily limb use.

“We can record data with these wireless sensors across numerous days and boil that down to a unique personalized profile of how a person is using their limbs or their prosthesis in the real world,” Frey said, “and then ideally we’ll be able to work with clinicians to develop more effective interventions and evaluate the effectiveness of those interventions in these individuals.”

“This is kind of a new adventure for me,” Frey continued. “This is an area that has grown out of my interest in connecting brain science with real-world behavior.”

The conduit for that connection, of course, is the wireless sensor, an Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) byproduct and hallmark of digital medicine. Sensors are just one of the many upshots of an IoMT-induced connected ecosystem that increasingly is being driven by healthcare data management, value-based care reimbursement models, and personalized medicine.

IoMT devices use embedded electronics and sensors to collect, record, and communicate real-time patient data. These electronic components have become smaller, more customized, and in some cases, more powerful to better facilitate interventions and reduce unnecessary clinical visits. The latter objective—now critical in light of the coronavirus pandemic—has spawned skyrocketing demand in the past year for telehealth services and remote patient monitoring technology.

Such demand consequently bolstered the role of electronics manufacturing services (EMS) providers as they worked to maintain device connectivity and helped customers navigate supply chain snafus and essential equipment shortages in COVID-19’s infancy.

This article is featured in the MPO eBook "Engaging Electronics." Click here to download the eBook and finish reading this article.