During the pandemic, the phrase “connected worker” has been thrown around quite a bit. With a good number of people working from home, it can be a reference to their new setting while still being linked to necessary systems at the office. This group maintains the ability to stay “connected” to the office and, more importantly, other employees, systems, and information while never leaving their home.

Others have a different definition, however. A connected worker can still travel to their workplace, but be equipped with the technology necessary to gain insights on all systems within a facility and keep updated on the status of jobs occurring at any moment. If there is a problem, the connected worker can be alerted immediately and respond quickly.

Taking time to explain the role of this type of connected worker, Steve Bieszczat, CMO of DELMIAworks, also shared many of the advantages this type of employee offers to a medical device manufacturers. In this Q&A, he explains how this type of worker has been vital during the pandemic but illustrates why this alignment would continue to be advantageous well after the pandemic is over. Empowering the employee to resolve issues and maintain a smooth workflow are benefits that would continue in years ahead.

Sean Fenske: What does it mean to be a connected worker within the medical device manufacturing space?

Steve Bieszczat: There is a long-standing thought of the connected worker as an employee that has fully bought into the job, the company, and their shared goals. That definition will live on forever.

A more recent definition of the connected worker, however, is a team member that is tied to their production work flow with some sort of technology. Perhaps a more precise term for this is the connected frontline worker. What it really means is that, on the shop floor, is a worker who is surrounded by the information they need to do their job and the digital ability to provide feedback about the status of the job or the product. For example, they have all the work instructions they need right on the screen in front of them, and they have a scanner to read and input quality assurance information without manually writing down measurements, hence the term “connected.” They are digitally connected and enabled to handle the job at hand. This is a key aspect of digital transformation.

When comparing production practices of the medical device industry versus the automotive or industrial goods industries, you’ll find they differ in several important aspects. First, medical device production is typically much more highly scrutinized. There are higher degrees of ascertainment in setting up production; higher degrees of quality assurance during production; and significant amounts of track and trace prior to, during, and post production. Second, medical device production is almost always carried out in a white or cleanroom environment. Third, particularly during the pandemic, medical device production was essential, and finding a way to produce was just not optional.

So while the impact of the connected worker concept is the same for most manufacturing sectors, the benefits to the medical device industry are compounded by the need for double rigor in medical production operations.

Fenske: What systems, technologies, or other capabilities must a company provide to truly connect a remote worker?

Bieszczat: At the highest level, you would consider these technologies to be ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) or MES (Manufacturing Execution System) solutions. But there are also standalone digital and visual work instruction software packages (and for that matter, quality management packages) that provide this sort of guided workflow assistance. DELMIAworks provides our solutions at the ERP and MES level.

Below the systems level, the technology becomes very discrete or physical: touch screens, scanners, computerized measuring devices, and sensors of all kinds.

Typically, the “read” side of the connected worker is software-driven; the feedback side is device-driven, and the backflush and analytics side is again software-driven.

There is a whole genre of the connected worker that is called “wearables,” but in the end, they are software-driven devices with the added convenience of keeping two hands available for machine operation or part manipulation.

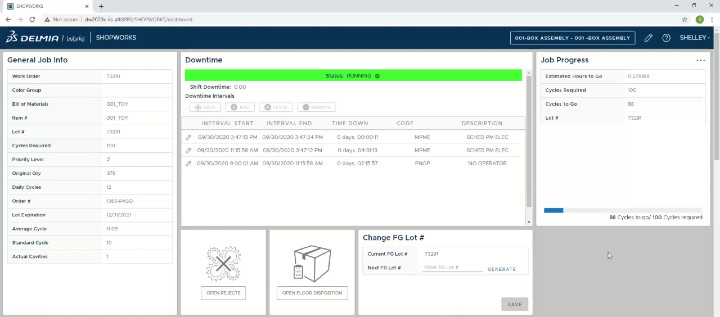

The SHOPWORKS module from DELMIAworks provides workers with documentation, instructions, and job performance metrics, allowing operators to be totally efficient at the work center.

Fenske: Has the COVID pandemic eliminated any reasons companies may have had to not enable a connected workforce?

Bieszczat: The COVID situation moved the connected worker concept to the forefront, and it did that in several ways. Early in the pandemic, it was a scramble just to get people in the front door and out on to the shop floor. Staggered shifts, temperature taking, personal protection equipment—call that the “protected worker.” Those protocols are easing or at least becoming more routine.

The second wave of COVID’s driving impetus for the connected worker came from stimulus checks and extended unemployment benefits. The manufacturing industry was already suffering from a shortage of labor at hourly rates of $12 to $15. Add to that people not working because they needed to stay home with children while they could still have a semi-comparable income, and you get an exacerbated labor shortage. So you saw the labor force sort of divided in two: those who really wanted to go to work and do a good job (the original connected worker) and those who, for one reason or another, opted out.

The challenge of the labor shortage meant production managers had to do more work with fewer people. One key element of doing more work with fewer people is worker agility—being able to quickly move from station to station. That is where the connected frontline worker really comes into play. As we discussed, technology for the connected frontline worker enables an operator to be totally efficient at the work center: performing the right steps, monitoring the right measurements, and performing the necessary post-production material handling. (By the way, our product provides these exact services at the work center with a module called SHOPWORKS). If a shop floor worker can walk up to a cold machine and know what to do immediately, then that worker becomes much more productive.

So the old saying, “Necessity is the mother of invention,” certainly came into play with COVID. The labor shortage required innovation. Connected worker concepts helped fill the gaps, and a new level of worker productivity became part of the mainstream manufacturing business model.

Fenske: What unexpected benefits have companies realized from establishing remote work functionality?

Bieszczat: At this point, I have to differentiate. Shop floor production cannot be done at home; this is why I called out the frontline worker. Those people could not work at home, and for the most part, neither did their direct supervision. Those frontline workers are part of the hero class of the pandemic.

Many other roles in the manufacturing workforce were able to work from home and advisably did so. By working remotely, they freed up social-distancing space for the production side while continuing to coordinate the flow of orders, materials, and production schedules.

ERP and MES ruled the day in this part of business. By logging onto ERP from home, front office workers were able to continue managing the business and to see and understand exactly what was happening on the shop floor through MES and all the connectedness of the connected worker. A key ERP and MES feature that drives the connected worker concept is “Alerts.” These are preset triggers that actively engage a worker with a task. For instance, a purchase order needs approval or we are running out of 12 gauge steel. Alerts call attention to issues that need immediate actions, and not only do they alert just once, they continue to alert until the issue has been addressed. Alerts connect the right employees to the right workflows at the right time. A great example of the power of the connected worker.

The continuity of manufacturing through the height of the pandemic was an incredibly well-orchestrated event between front office staff and shop floor workers that was largely made possible by the modern ERP and MES technologies we see deployed in factories today.

Fenske: Once we are past the pandemic, will companies still be enthusiastic about establishing remote work functionality?

Bieszczat: I’m not certain enthusiastic is the right word. Within manufacturing, there is a culture of being at the factory. It is part of the industry ethic, and I think, to a great extent, one of the reasons people decide to work in manufacturing. The aesthetics of it—the sounds, the smells, the sense of making something—are all very important parts of what it means to be in manufacturing.

That said, and a step back from the word enthusiastic, is the practicality of working remotely. It certainly creates a more flexible work environment (for example, for parents with child care concerns and people with a temporary need to be out of the office and still attend to workplace essentials). It also provides access to qualified, but perhaps only part-time job seekers. The proven ability to productively work remotely has permanently changed the manufacturing front office landscape. And it will make manufacturing a more appealing career to many talented people who, for one reason or another, might not be able to get to the factory all day, every day.

Fenske: Do companies have regulatory or quality concerns with relation to connected/remote workers?

Bieszczat: As we discussed earlier, the lion’s share of production is done in the factory. I have seen some assembly work done at home, usually piece work, but that’s not a major part of the industry. As far as the connected frontline worker, driving quality and productivity is what the technology is all about. So to answer your question, the quality impact of remote workers is small. The quality impact of the connected worker is a plus, plus.

Learn more about DELMIAworks >>>>>