Jayme Richter and Bridseida Melendez, B. Braun Medical Inc.04.03.17

Imagine being a restaurant owner and a customer complains to you about the flavor of the chicken marsala that evening. You instinctually begin to think about how one of your cooks may have screwed up during the preparation. Did they overcook it? Undercook it? Put in too much marsala? Forget the marsala altogether?

While your assumption of blame may seem logical based on the complaint, it could be misplaced. The preparation of the dish might have been perfect. Were the ingredients bad or spoiled? Did it spend too much time under a heat lamp? Did it interact poorly with other flavors on the plate? Did the server inadequately manage expectations about the dish? Did a cold plate cause the dish to cool prematurely?

There could be any number of variables that influence the quality of a final product. Whether it’s a restaurant entrée or medical device, it is essential to identify the real reason (or reasons) for the problem so they can be rectified.

That’s where the process of “root cause analysis” (RCA) comes in. RCA is a methodology for identifying the cause or causes of an incident to determine the most effective solution. While it’s typically deployed as the response to a problem, it can also be used to identify processes that are successful.

The RCA process is especially useful in the medical device outsourcing field. Although contract manufacturers and their customers often work very closely and collaboratively, contract manufacturers are typically removed from the medical device end user. An established, integrated methodology such as RCA helps bring essential structure to the problem-solving process—and helps manage expectations across the respective organizations. RCA gives customers and contract manufacturers a definitive road map to follow.

Beyond Typical Problem-Solving Approaches

It’s human nature to want to solve problems as quickly as possible. That inclination is even more pronounced when a business relationship exists between a contract manufacturer and a customer. Add the human health and safety element involved with a medical device and you have every incentive for reaching a solution as quickly as possible.

However, the search for a fast remedy often results in incomplete or incorrect resolutions. How many times have you heard the following statements:

Team Approach Essential

One of the most important realizations in the RCA process is that problems can come from anywhere. Quality management systems and their data—discrepancies, complaints, CAPAs, audits, and other customer-centered feedback—are often a starting point, but they are not the only source. Internal measures and observations, such as safety incidents or efficiency evaluations, can also spur the RCA process.

Since the real cause or causes of the problem could stem from many areas, it is essential to form a cross-functional team that represents the functional areas involved throughout the product lifecycle. The width and depth of the team depends on the severity of the problem.

Cross-functional teams allow the issue to be viewed from different angles with various types of expertise and fresh eyes. Sometimes people outside of the core team can see things right away. Depending on the issue, one may bring in experts from production, quality, engineering (both process and R&D), supply chain, and more.

Importantly, team members need to realize they have nearly equal standing on the team. One’s position in the organization or years of industry experience should not be as important on the RCA team as it might be elsewhere in the company. Decisions need to be based on data and not someone’s stature within the organization.

Problem Statement Is Key

To know what to study and analyze, one needs to know what they’re looking for. Clearly defining the source of the problem will lead to a less complicated evaluation. A well-defined problem statement gets the company halfway to resolution.

The problem statement should precisely identify five Ws and one H—with specific quantification whenever possible:

If you don’t distinctly define the problem, the process is suspect to scope creep. The more narrowly you can define the problem, the better. For example, if the problem is in manufacturing, can you determine if it is isolated to a specific shift, machine, or team?

In a contract manufacturing relationship, open and complete communication between customers and their outsourcing partners cannot be overstated. Customers need to be diligent about collecting data and sharing it with the contract manufacturer. A phone call regarding end-use customers complaining about the integrity of product packaging is not enough; this issue needs to be more narrowly defined. When did the complaints originate? How many complaints have arisen? What specific products? What about the packaging was compromised? The more information the customer can share with the outsourcing partner, the better.

Defining the problem often involves integrating the voice of the customer. It doesn’t matter whether the “customer” is an internal one or external. When you go directly to the people who are raising the issues, you receive an unfiltered perspective on what is happening. The voice of the customer is critical to defining the problem and, as will be clear, solutions.

Ultimately, the team will develop a “target condition”—a focused, quantitative, and measurable description of the desired state of the process or system. It is a refinement of the problem statement that identifies the goal that is to be achieved by the RCA process and team.

Identifying Root Causes

Since each problem may have multiple causes, each with various levels of prominence or clarity, it is crucial to rely on data and direct observation whenever possible. The cross-functional team is charged with brainstorming potential causes for the problem based on the expertise they bring to the investigation and by using data to objectively inform the RCA process.

Data is the big equalizer on the cross-functional team. It can be difficult for a relatively new employee to challenge someone with decades of experience. Opinions are interpretations; data speaks for itself. The collective analysis of data interjects a level of equality into the process, giving everyone’s expertise balanced weight. Data will help determine when the issue is resolved or improvements have been realized. Data is required to measure success.

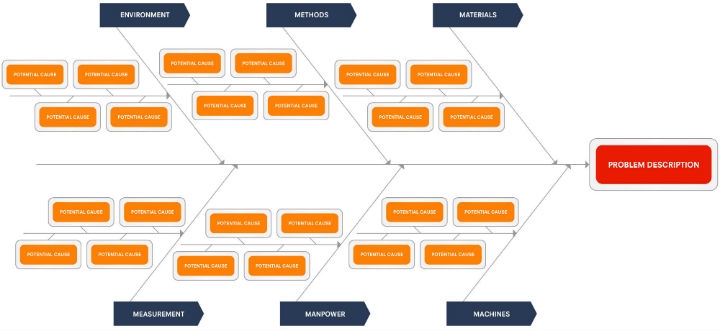

RCA teams can use a number of tools based on the severity of the problem. A frequently used tool is the cause-and-effect or fishbone diagram (Figure 1), which depicts the potential influences in a simple-to-understand visual manner for the team. A company may have several cause-and-effect diagram models depending upon the problem, for example, ones that focus primarily on manufacturing processes or service processes, or one that organizes multiple processes into major and minor cause categories.

Once the RCA team identifies a model, it needs to begin developing potential root causes collectively. All reasonable causes must be considered when generating the diagram. At this point, the team members should push for deeper understanding of the potential causes by sharing their evaluation of the data based on their area of expertise. In addition, the voice of the customer can be helpful in developing potential solutions. Internal or external customers can provide valuable input on potential resolutions based on their needs. Sometimes, “the voice” involves observing how people interact with a device in the field or assemble a device on the line.

The process for prioritizing the potential causes depends upon the severity of the problem. Simpler problems often use a “nominal group technique” whereby each member ranks the list of potential root causes according to the order in which they believe they should be tackled. The votes are tallied and the causes are sequenced and addressed in priority order until the team’s goal—the target condition or resolution—has been met.

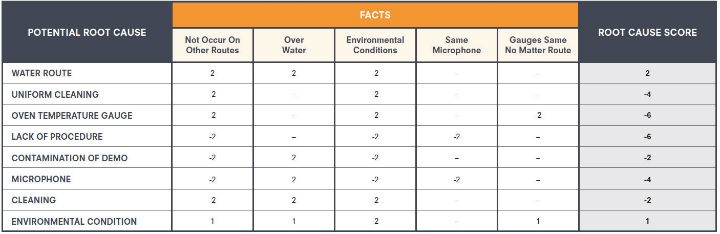

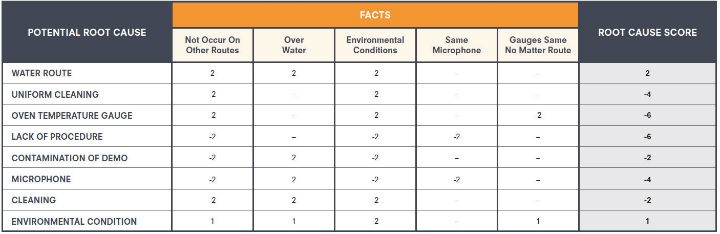

For more complex problems, the team may deploy a contradiction matrix (Figure 2) that lists root causes along the vertical axis and facts, observations, and test results related to the potential causes along the horizontal axis. For each potential cause, facts that support or contradict the problem are scored +2 or -2, respectively, and assumptions that support or contradict the potential cause are scored +1 or -1. After scoring each fact against each potential cause, total scores are tabulated for each potential root cause. The potential causes are sorted and prioritized in descending order.

Figure 2: Contradiction matrix example—For each potential cause, facts that support or contradict the problem are scored +2 or -2, respectively. Assumptions that support or contradict the potential cause are scored +1 or -1, respectively. The dash indicates the fact is not applicable to cause. Total scores are then tabulated for each potential root cause. (Click the chart to view a larger version.)

Finding Permanent Solutions

Using the refined lists from the nominal group technique or the contradiction matrix, the team conducts rapid experiments to establish and verify (or rule out) the identity of the root causes of the problem and test for potential solutions. Experiments provide objective evidence supporting that the root cause being evaluated is properly understood and that the proposed solution moves the team closer to solving the problem and reaching the target condition.

Based on the results of each experiment, the team will determine the next course of action, which may include further experimentation or moving on to implement corrective actions if the experiment establishes the true root cause or solution.

After the rapid experiment process and the requisite documentation of the results, the team will identify actions required to introduce permanent corrective actions for each applicable root cause. The actions should identify what is to be accomplished, who is responsible for accomplishing it, the target date for implementation, and the status of the action. For problems where the team does not have authority for the required actions, the problem owner is responsible for taking the team’s plan to cross-functional areas to ensure implementation.

Verification of success is the final step to ensure that the root causes have been sufficiently mitigated, reduced, or eliminated according to the target condition. Tools and techniques for monitoring effectiveness can include statistical process control, audits, sampling, management review, and design verification/validation or process validation.

As a final outcome, teams share the knowledge and experience gained as a part of continuous improvement activities across the organization. The outcomes can help shed light on other areas in the company where the problem may exist and seek a more effective, streamlined solution using the RCA process. In some cases, the learnings gleaned from the RCA process may be institutionalized in other areas of the company, which is why data and documentation are essential throughout the process.

RCA in Practice

The RCA methodology is logical and powerful. However, it requires patience and dedication to see it through from beginning to end. As noted, the human tendency to want to find a quick solution can shortcut RCA.

For example, assume that a contract manufacturer received a customer complaint about a device component poking through the top of the packaging, voiding the sterilization and the product. A senior engineer at the organization deemed the problem must be that the packaging material is too weak. A move is made to an alternate, stronger material. But in the field, the problem returns, prompting the team to implement the RCA process. With a cross-functional team and data analysis, the team determined that the material on the bottom of the packaging was shrinking during sterilization, weakening the material where the component was poking through. Also, it was noticed that the part poking through the top had a sharp edge on one side; assembly associates were not being careful enough placing them in the package. Both situations were resolved through experimentation and eventual adoption, and the problem was fixed. The team learned that bypassing RCA to expedite a solution ended up costing more time and money.

Another example: six discrepancies a month with labeling through a medical device manufacturer’s print shop were costing the company $120,000 a year in rework costs, material losses, and time to investigate and remedy individual issues. After developing a tight problem statement, a team was composed to determine the root cause or causes and arrive at remedies. By looking at the problem holistically, the team arrived at three causes and solutions. First, the old labeling system was not fully compatible with the printers. New labeling software was found to fix the problem. Next, some of the legacy print equipment used in the process was nearing the end of its life span. New printers—already identified as a future purchase—were expedited and installed. Finally, as the team worked through the entire process and flow diagram, they identified many non-value-added activities. By implementing new standard operating procedures, the team reduced waste and improved efficiency. The target condition of two discrepancies per month (down from six) was actually reduced to one-half a month. While there was expense involved in reaching the solution, having the problem statement and data enabled the team to justify the purchase to management and prove the RCA approach was fruitful and valuable.

An Integrated Approach

As one might expect, RCA is closely aligned with Lean and Six Sigma philosophies for reducing waste and improving quality. It is a prescriptive approach that relies on a series of tools as well as the open-mindedness and discipline of a cross-functional team to develop real and lasting solutions. When used in the contract manufacturing setting, RCA demands that the customer contribute to the process with data and information.

By understanding the RCA process and their role in collecting data and validating solutions, outsourcing customers can be part of a process that will ultimately result in better outcomes and improved processes long into the future.

Jayme Richter is QA validation manager at B. Braun Medical Inc. A Six Sigma green belt, she has been in the biotechnology, pharmaceutical, and medical device fields since 1999.

Bridseida Melendez is director, Quality Assurance, for the Allentown (Pa.) operations of B. Braun Medical Inc. A 16-year medical device industry veteran, she is a Six Sigma green belt and is certified Design Control & Validation.

While your assumption of blame may seem logical based on the complaint, it could be misplaced. The preparation of the dish might have been perfect. Were the ingredients bad or spoiled? Did it spend too much time under a heat lamp? Did it interact poorly with other flavors on the plate? Did the server inadequately manage expectations about the dish? Did a cold plate cause the dish to cool prematurely?

There could be any number of variables that influence the quality of a final product. Whether it’s a restaurant entrée or medical device, it is essential to identify the real reason (or reasons) for the problem so they can be rectified.

That’s where the process of “root cause analysis” (RCA) comes in. RCA is a methodology for identifying the cause or causes of an incident to determine the most effective solution. While it’s typically deployed as the response to a problem, it can also be used to identify processes that are successful.

The RCA process is especially useful in the medical device outsourcing field. Although contract manufacturers and their customers often work very closely and collaboratively, contract manufacturers are typically removed from the medical device end user. An established, integrated methodology such as RCA helps bring essential structure to the problem-solving process—and helps manage expectations across the respective organizations. RCA gives customers and contract manufacturers a definitive road map to follow.

Beyond Typical Problem-Solving Approaches

It’s human nature to want to solve problems as quickly as possible. That inclination is even more pronounced when a business relationship exists between a contract manufacturer and a customer. Add the human health and safety element involved with a medical device and you have every incentive for reaching a solution as quickly as possible.

However, the search for a fast remedy often results in incomplete or incorrect resolutions. How many times have you heard the following statements:

- “We keep solving the same problems over and over again.”

- “We solved the wrong problem altogether.”

- “It takes us too long to solve problems; we keep going around in circles.”

- “Problem solving should be concentrated in quality because the problem is with product quality.”

- “I’m the person responsible for the quality. I will solve the problem.”

- Problem awareness and recognition

- Team formation

- Writing the problem statement

- Identifying root causes—and their causes

- Examining potential solutions and experimenting on them

- Developing and implementing corrective actions

- Verification of the actions

- Standardization of the new actions

- Sharing of expertise across the organization

Team Approach Essential

One of the most important realizations in the RCA process is that problems can come from anywhere. Quality management systems and their data—discrepancies, complaints, CAPAs, audits, and other customer-centered feedback—are often a starting point, but they are not the only source. Internal measures and observations, such as safety incidents or efficiency evaluations, can also spur the RCA process.

Since the real cause or causes of the problem could stem from many areas, it is essential to form a cross-functional team that represents the functional areas involved throughout the product lifecycle. The width and depth of the team depends on the severity of the problem.

Cross-functional teams allow the issue to be viewed from different angles with various types of expertise and fresh eyes. Sometimes people outside of the core team can see things right away. Depending on the issue, one may bring in experts from production, quality, engineering (both process and R&D), supply chain, and more.

Importantly, team members need to realize they have nearly equal standing on the team. One’s position in the organization or years of industry experience should not be as important on the RCA team as it might be elsewhere in the company. Decisions need to be based on data and not someone’s stature within the organization.

Problem Statement Is Key

To know what to study and analyze, one needs to know what they’re looking for. Clearly defining the source of the problem will lead to a less complicated evaluation. A well-defined problem statement gets the company halfway to resolution.

The problem statement should precisely identify five Ws and one H—with specific quantification whenever possible:

- What happened?

- When did it happen?

- Where did it take place?

- Who was involved?

- Why did it happen?

- How did it happen?

If you don’t distinctly define the problem, the process is suspect to scope creep. The more narrowly you can define the problem, the better. For example, if the problem is in manufacturing, can you determine if it is isolated to a specific shift, machine, or team?

In a contract manufacturing relationship, open and complete communication between customers and their outsourcing partners cannot be overstated. Customers need to be diligent about collecting data and sharing it with the contract manufacturer. A phone call regarding end-use customers complaining about the integrity of product packaging is not enough; this issue needs to be more narrowly defined. When did the complaints originate? How many complaints have arisen? What specific products? What about the packaging was compromised? The more information the customer can share with the outsourcing partner, the better.

Defining the problem often involves integrating the voice of the customer. It doesn’t matter whether the “customer” is an internal one or external. When you go directly to the people who are raising the issues, you receive an unfiltered perspective on what is happening. The voice of the customer is critical to defining the problem and, as will be clear, solutions.

Ultimately, the team will develop a “target condition”—a focused, quantitative, and measurable description of the desired state of the process or system. It is a refinement of the problem statement that identifies the goal that is to be achieved by the RCA process and team.

Identifying Root Causes

Since each problem may have multiple causes, each with various levels of prominence or clarity, it is crucial to rely on data and direct observation whenever possible. The cross-functional team is charged with brainstorming potential causes for the problem based on the expertise they bring to the investigation and by using data to objectively inform the RCA process.

Data is the big equalizer on the cross-functional team. It can be difficult for a relatively new employee to challenge someone with decades of experience. Opinions are interpretations; data speaks for itself. The collective analysis of data interjects a level of equality into the process, giving everyone’s expertise balanced weight. Data will help determine when the issue is resolved or improvements have been realized. Data is required to measure success.

RCA teams can use a number of tools based on the severity of the problem. A frequently used tool is the cause-and-effect or fishbone diagram (Figure 1), which depicts the potential influences in a simple-to-understand visual manner for the team. A company may have several cause-and-effect diagram models depending upon the problem, for example, ones that focus primarily on manufacturing processes or service processes, or one that organizes multiple processes into major and minor cause categories.

Once the RCA team identifies a model, it needs to begin developing potential root causes collectively. All reasonable causes must be considered when generating the diagram. At this point, the team members should push for deeper understanding of the potential causes by sharing their evaluation of the data based on their area of expertise. In addition, the voice of the customer can be helpful in developing potential solutions. Internal or external customers can provide valuable input on potential resolutions based on their needs. Sometimes, “the voice” involves observing how people interact with a device in the field or assemble a device on the line.

The process for prioritizing the potential causes depends upon the severity of the problem. Simpler problems often use a “nominal group technique” whereby each member ranks the list of potential root causes according to the order in which they believe they should be tackled. The votes are tallied and the causes are sequenced and addressed in priority order until the team’s goal—the target condition or resolution—has been met.

For more complex problems, the team may deploy a contradiction matrix (Figure 2) that lists root causes along the vertical axis and facts, observations, and test results related to the potential causes along the horizontal axis. For each potential cause, facts that support or contradict the problem are scored +2 or -2, respectively, and assumptions that support or contradict the potential cause are scored +1 or -1. After scoring each fact against each potential cause, total scores are tabulated for each potential root cause. The potential causes are sorted and prioritized in descending order.

Figure 2: Contradiction matrix example—For each potential cause, facts that support or contradict the problem are scored +2 or -2, respectively. Assumptions that support or contradict the potential cause are scored +1 or -1, respectively. The dash indicates the fact is not applicable to cause. Total scores are then tabulated for each potential root cause. (Click the chart to view a larger version.)

Finding Permanent Solutions

Using the refined lists from the nominal group technique or the contradiction matrix, the team conducts rapid experiments to establish and verify (or rule out) the identity of the root causes of the problem and test for potential solutions. Experiments provide objective evidence supporting that the root cause being evaluated is properly understood and that the proposed solution moves the team closer to solving the problem and reaching the target condition.

Based on the results of each experiment, the team will determine the next course of action, which may include further experimentation or moving on to implement corrective actions if the experiment establishes the true root cause or solution.

After the rapid experiment process and the requisite documentation of the results, the team will identify actions required to introduce permanent corrective actions for each applicable root cause. The actions should identify what is to be accomplished, who is responsible for accomplishing it, the target date for implementation, and the status of the action. For problems where the team does not have authority for the required actions, the problem owner is responsible for taking the team’s plan to cross-functional areas to ensure implementation.

Verification of success is the final step to ensure that the root causes have been sufficiently mitigated, reduced, or eliminated according to the target condition. Tools and techniques for monitoring effectiveness can include statistical process control, audits, sampling, management review, and design verification/validation or process validation.

As a final outcome, teams share the knowledge and experience gained as a part of continuous improvement activities across the organization. The outcomes can help shed light on other areas in the company where the problem may exist and seek a more effective, streamlined solution using the RCA process. In some cases, the learnings gleaned from the RCA process may be institutionalized in other areas of the company, which is why data and documentation are essential throughout the process.

RCA in Practice

The RCA methodology is logical and powerful. However, it requires patience and dedication to see it through from beginning to end. As noted, the human tendency to want to find a quick solution can shortcut RCA.

For example, assume that a contract manufacturer received a customer complaint about a device component poking through the top of the packaging, voiding the sterilization and the product. A senior engineer at the organization deemed the problem must be that the packaging material is too weak. A move is made to an alternate, stronger material. But in the field, the problem returns, prompting the team to implement the RCA process. With a cross-functional team and data analysis, the team determined that the material on the bottom of the packaging was shrinking during sterilization, weakening the material where the component was poking through. Also, it was noticed that the part poking through the top had a sharp edge on one side; assembly associates were not being careful enough placing them in the package. Both situations were resolved through experimentation and eventual adoption, and the problem was fixed. The team learned that bypassing RCA to expedite a solution ended up costing more time and money.

Another example: six discrepancies a month with labeling through a medical device manufacturer’s print shop were costing the company $120,000 a year in rework costs, material losses, and time to investigate and remedy individual issues. After developing a tight problem statement, a team was composed to determine the root cause or causes and arrive at remedies. By looking at the problem holistically, the team arrived at three causes and solutions. First, the old labeling system was not fully compatible with the printers. New labeling software was found to fix the problem. Next, some of the legacy print equipment used in the process was nearing the end of its life span. New printers—already identified as a future purchase—were expedited and installed. Finally, as the team worked through the entire process and flow diagram, they identified many non-value-added activities. By implementing new standard operating procedures, the team reduced waste and improved efficiency. The target condition of two discrepancies per month (down from six) was actually reduced to one-half a month. While there was expense involved in reaching the solution, having the problem statement and data enabled the team to justify the purchase to management and prove the RCA approach was fruitful and valuable.

An Integrated Approach

As one might expect, RCA is closely aligned with Lean and Six Sigma philosophies for reducing waste and improving quality. It is a prescriptive approach that relies on a series of tools as well as the open-mindedness and discipline of a cross-functional team to develop real and lasting solutions. When used in the contract manufacturing setting, RCA demands that the customer contribute to the process with data and information.

By understanding the RCA process and their role in collecting data and validating solutions, outsourcing customers can be part of a process that will ultimately result in better outcomes and improved processes long into the future.

Jayme Richter is QA validation manager at B. Braun Medical Inc. A Six Sigma green belt, she has been in the biotechnology, pharmaceutical, and medical device fields since 1999.

Bridseida Melendez is director, Quality Assurance, for the Allentown (Pa.) operations of B. Braun Medical Inc. A 16-year medical device industry veteran, she is a Six Sigma green belt and is certified Design Control & Validation.